This album is divided into two parts. The first part includes a biographical overview of Ostad Elahi. This section is relatively short, since a more complete account of his life is beyond the scope of this album.

The second part of the album includes a collection of photographs illustrating the different periods of Ostad Elahi’s life. Some of these photos closely resemble others, which may occasionally give an impression of repetition. Our goal here, however, is to present as complete and comprehensive a selection as possible.

Furthermore, several pages of this album are devoted to Ostad Elahi’s judicial career. In this section, some additional biographical material has been included which deals specifically with that period of his life. These texts include some of Ostad Elahi’s sayings, which were written down by his students. They should help the reader get a better grasp of the uncompromising way he performed his duties and the rigor with which he rendered justice.

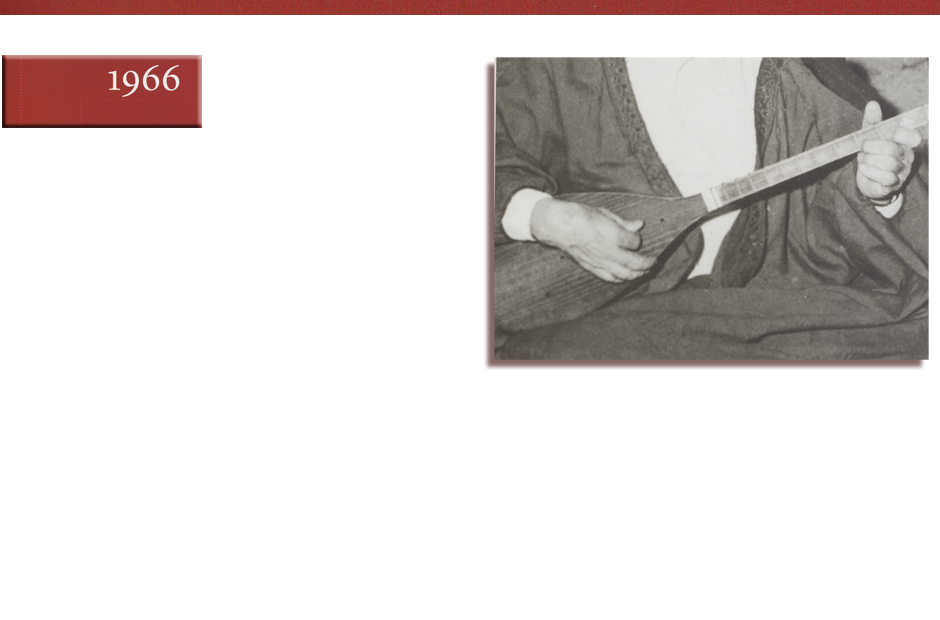

Some of Ostad Elahi’s sayings can also be found accompanying the photographs in which he is seen playing the tanbur, a type of lute traditionally used for sacred music. The writings in this section may help the reader appreciate the centrality of music in the life of this great thinker, who was recognised by contemporary musicians as a peerless master of sacred music and the art of the tanbur.

Sincere thanks to the many people who participated in preparing this album, and especially to those who helped by providing some of the undoubtedly treasured photographs.

If other readers have, or know of, any other photographs of Ostad Elahi which have not been included in this initial edition, it would be particularly appreciated if they could lend such photos for copying, so that they may be included in future editions of this collection.

Professor Bahram Elahi

My father used to say to me, “It is as if I have raised you in a fine garden. If you look beyond the garden walls, you’ll see nothing but dirt and filth”. When I entered society, I didn’t even know that it was possible for people to lie or cheat or do anything immoral. On account of this, I suffered a good deal.

Extract from Asar ol-Haqq (Traces of the Truth), a collection of Ostad Elahi’s teachings, vol. I, ch.24.

Childhood Residence

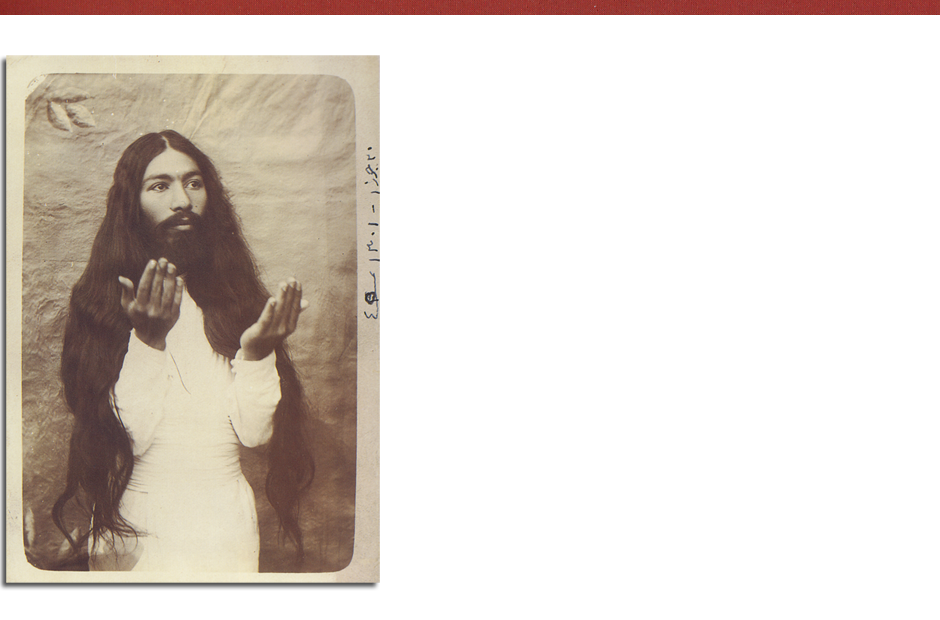

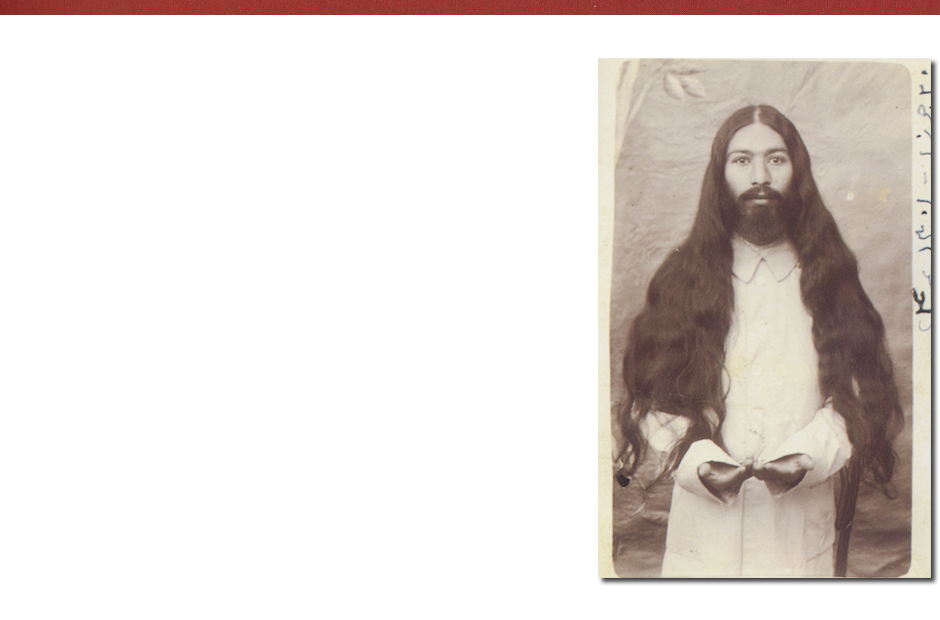

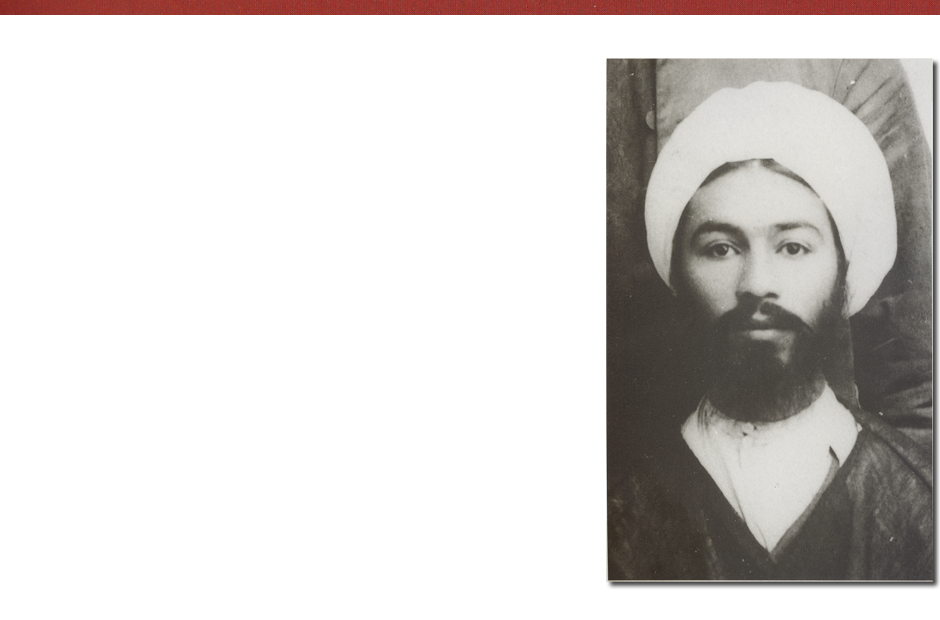

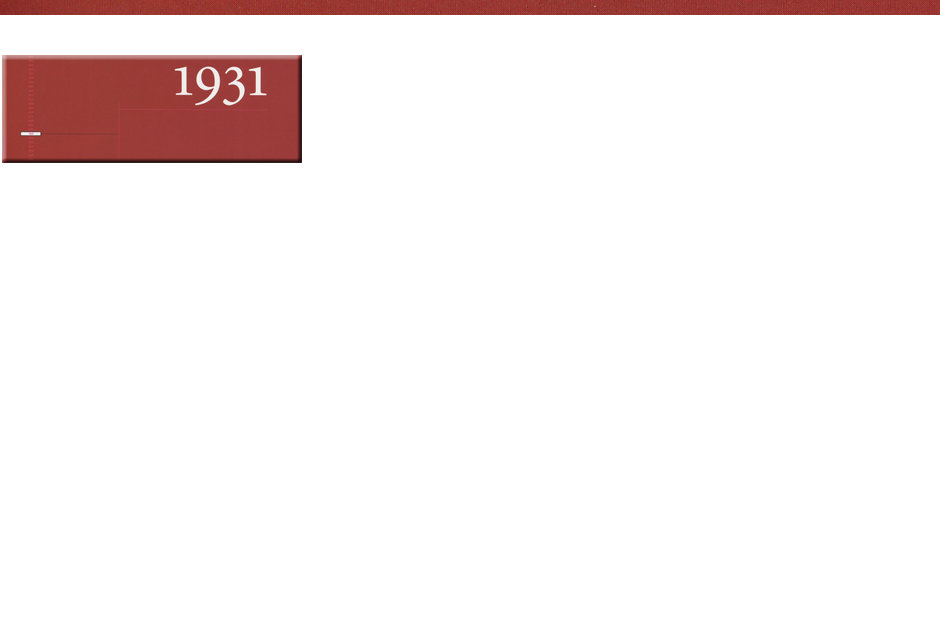

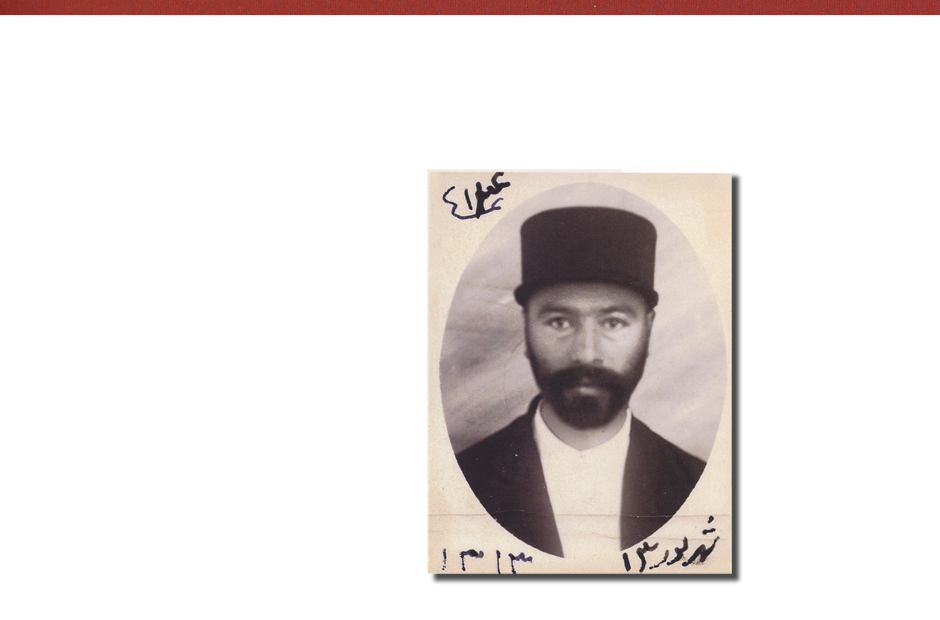

The year Ostad Elahi left his birthplace for the first time and went to Tehran. These are the earliest photographs of him. His hair had not been cut since the age of 6.

The year Ostad Elahi left his birthplace for the first time and went to Tehran. These are the earliest photographs of him. His hair had not been cut since the age of 6.

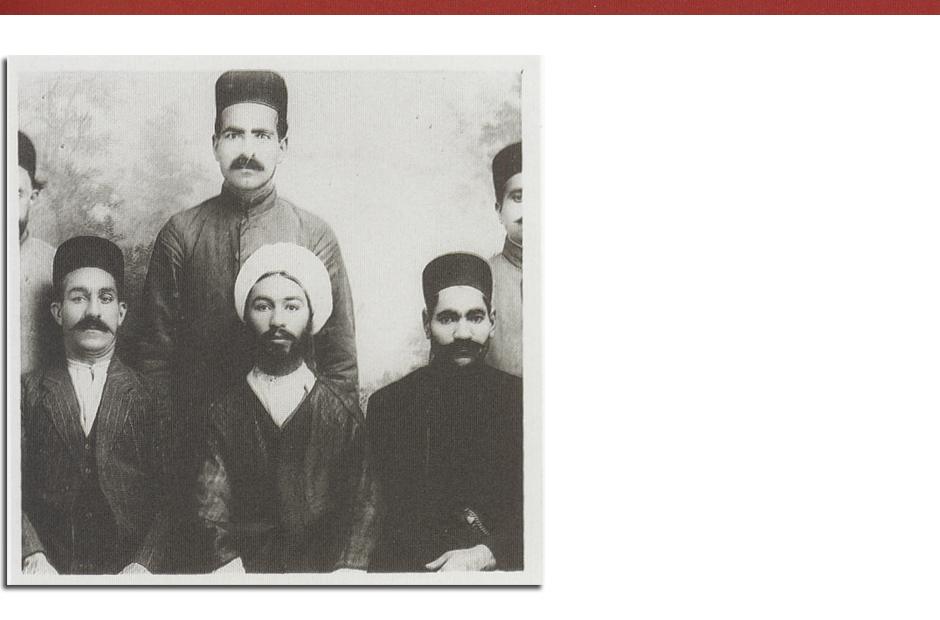

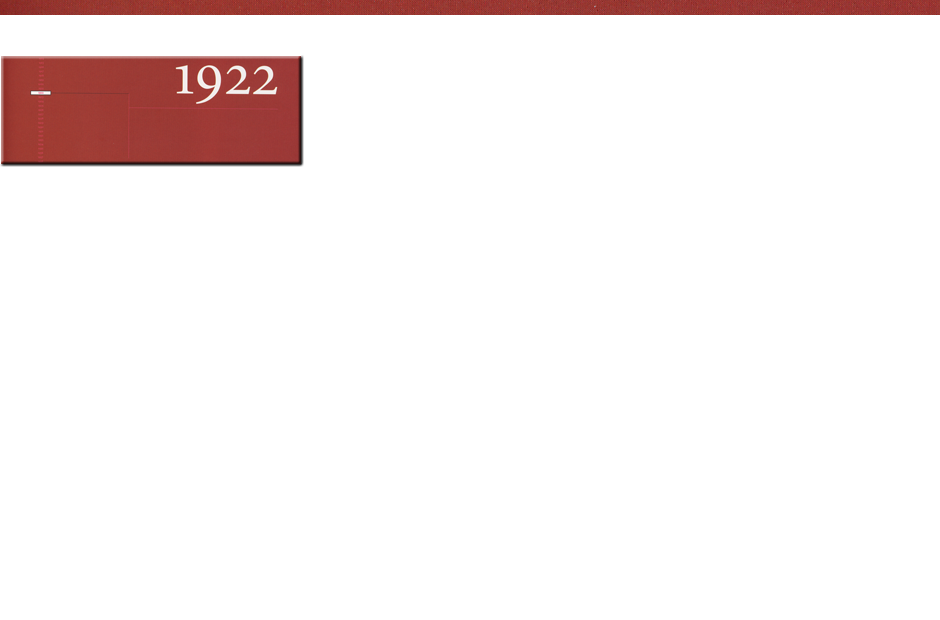

Among a few followers.

The photograph in which I have long hair and wear a turban, goes back to the time when I had started the twenty-sixth year of my life. I was in an angelic world, and was in a state of constant asceticism, eating only one frugal meal a day just after sunset, consisting of vegan food only. Even so, I had a fresh and rosy complexion and felt fit and well all the time.

Extract from Asar ol-Haqq, vol. 1, ch.24. This chapter contains many accounts of Ostad Elahi’s life, in his own words

Detail from a collective photograph: he considered this photograph to be rather special.

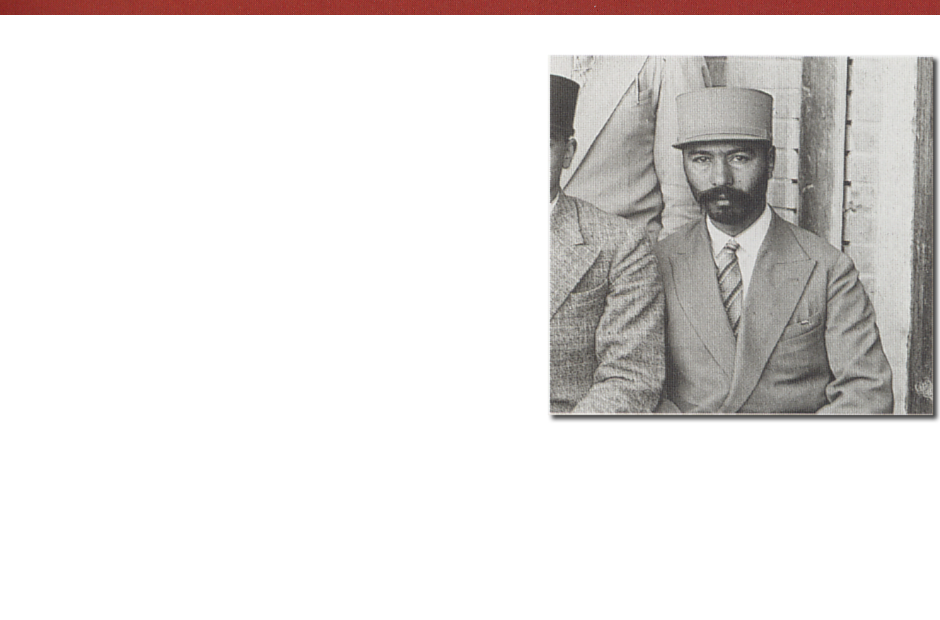

At this time, Ostad Elahi worked in the Western province of Kermânshâh at the Central Registry. Two years prior to that, at the age of thirty-four, he cut his hair and beard.

At this time, Ostad Elahi worked in the Western province of Kermânshâh at the Central Registry. Two years prior to that, at the age of thirty-four, he cut his hair and beard.

The date written on the photograph is in Ostad’s handwriting. According to official files, Ostad Elahi was laid off for three months for insubordination, due to disagreements with the corrupt head of the Kermânshâh Central Registry.

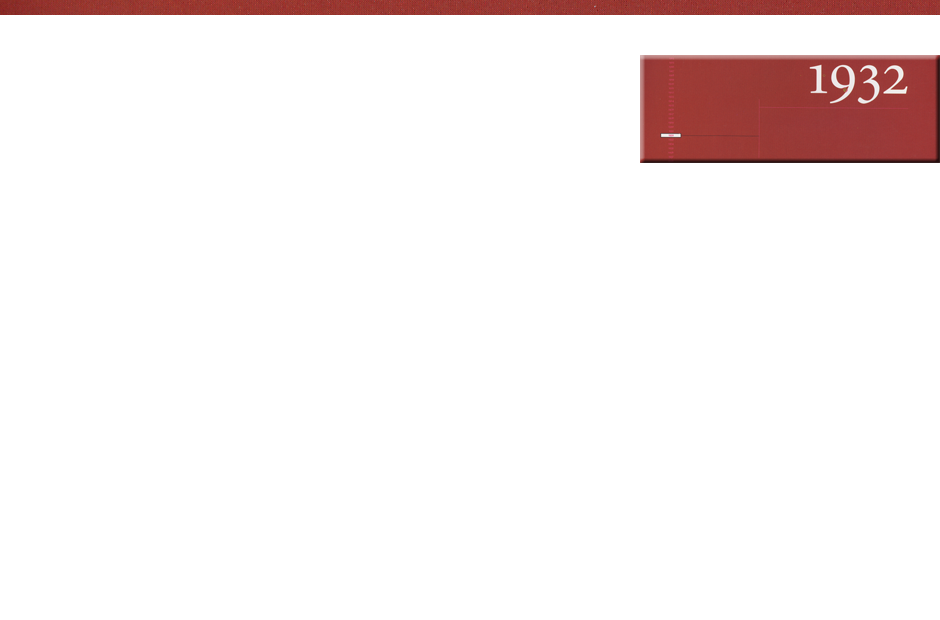

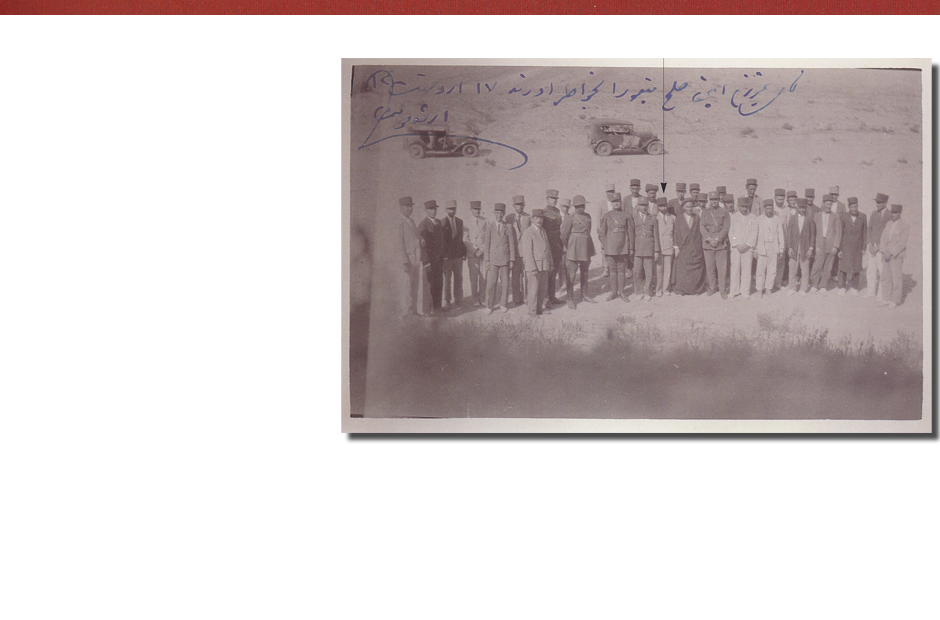

August 1934, Tehran, during a twenty-five day Judicial Internship at the Tehran Court of Peace

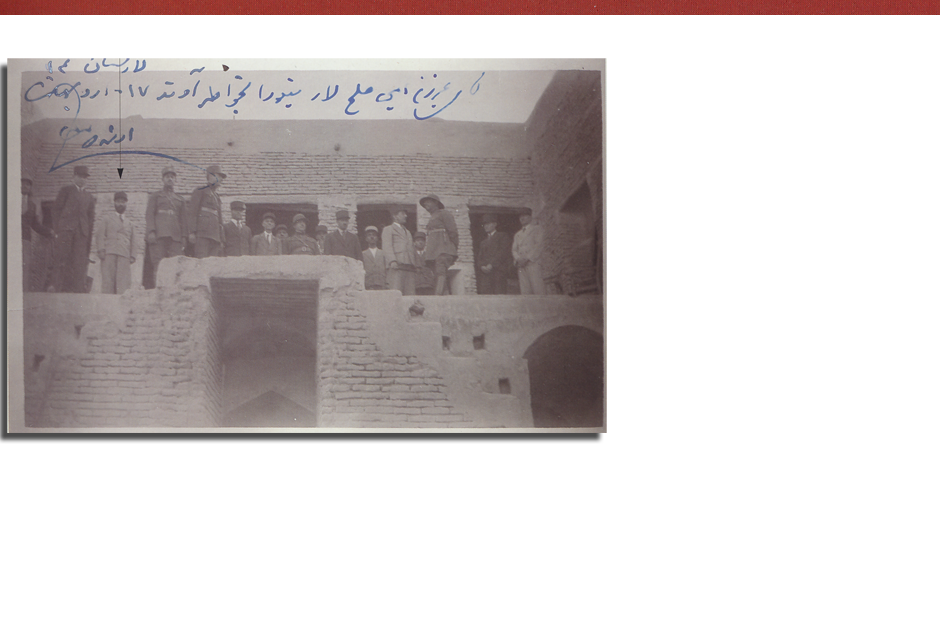

May 1935. Ostad Elahi was Justice of the Peace in Lâr, a small town in the south of Iran.

The inscription on the photograph is not in his handwriting.

May 1935. Ostad Elahi was Justice of the Peace in Lâr, a small town in the south of Iran.

The inscription on the photograph is not in his handwriting.

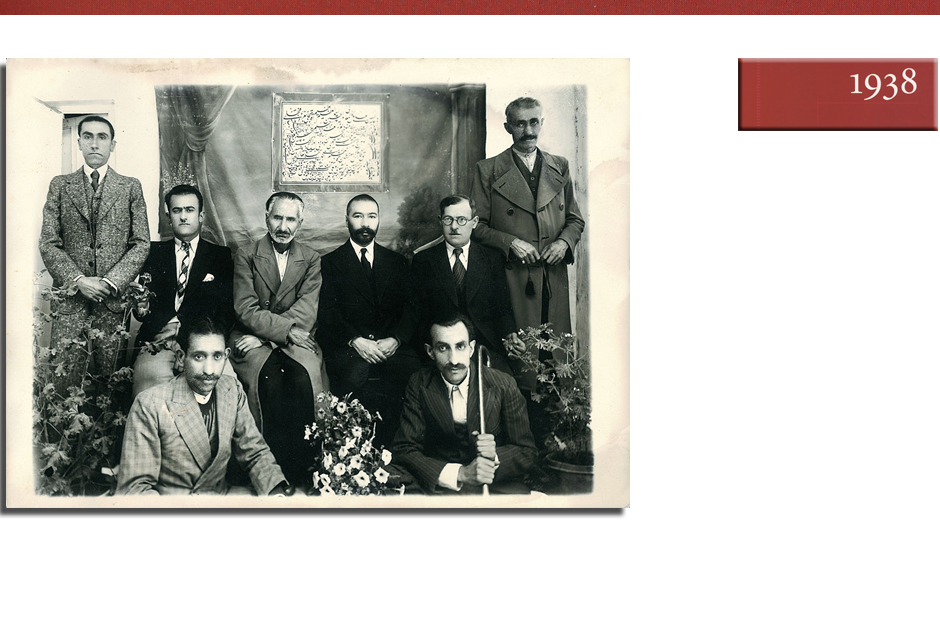

He was then a Surrogate Judge of the Preliminary Court and Examining Magistrate in Shiraz

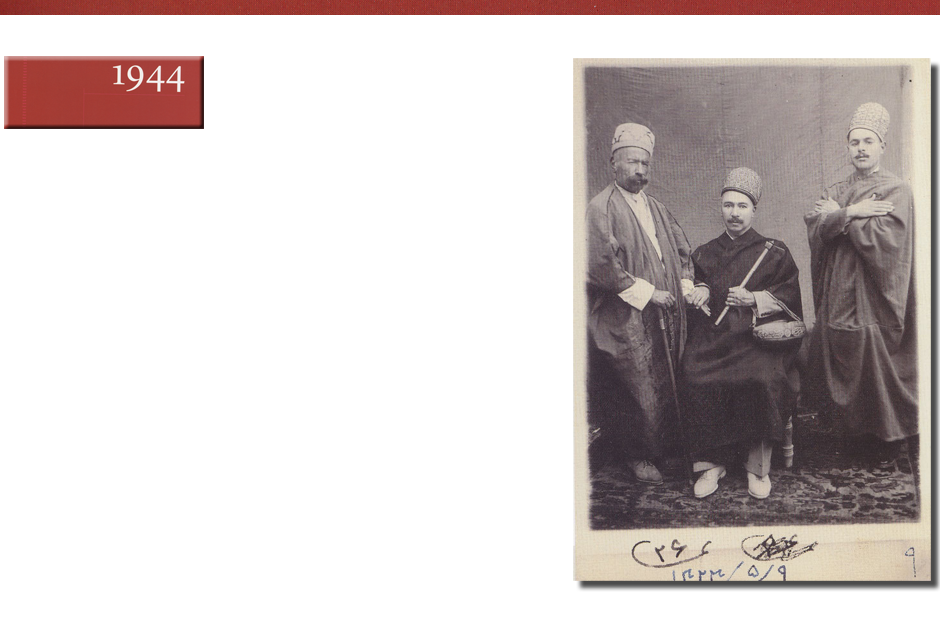

July 3, 1944. In the traditional clothing of the dervishes with his eldest son and an acquiantance

Throughout my career as a civil servant, I did not use any office pen for my personal affairs, and I never shortened my office hours by a second. Sometimes, I took additional work home in order to compensate for any loss of office time that might have been caused inadvertently. For I had willingly sold my time in exchange for the salary I was receiving and, by cutting down on the office hours, I would have been doing something that in essence was no different from stealing.

As a judge, I made use of psychology, always trying to reform offenders rather than persecuting them.

In the execution of my duties as a judge, I would do things that no one else dared to do, for I was answerable to God, not to the Ministry, and was not afraid of anyone.

– Short quotations from Ostad Elahi, Asar ol-Haqq, vol I.

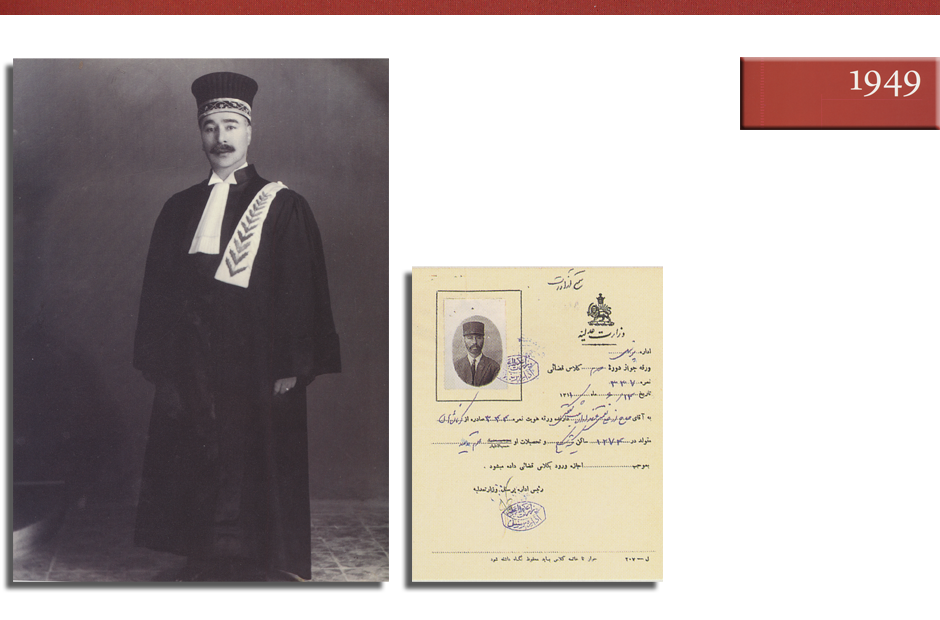

Far left photograph – In his Judicial Robe. He was then Head of the Justice Administration in the city of Jahrom

Sample document from official files

God made me enter the judicial service despite my aversion to it. He forced me to become a judge and assigned me to highly sensitive judicial positions. I found out, later on, that each of those experiences contained so many subtle points of wisdom that a thousand philosophers, putting their heads together, could not have brought them out.

_________________

If a judge is concerned only with the truth, God will help him in critical moments by showing him the right way.

_________________

Throughout the course of my career as a judge, I always began my day’s work with these words: “O God, I place myself in Your hands. Since I want nothing but Your satisfaction, please forgive me whenever I make a mistake:” God be praised, for He prevented me from making judicial mistakes.

_________________

[…] During the entire course of my tenure as a judge, I did not pass a single death sentence.

_________________

Wherever I worked, I saw to it that the atmosphere was warm and that my staff and I were friendly towards each other. They would often come with their families to our house. In the morning, they would arrive early at the office and leave late in the afternoon. As for myself, I was so engrossed in my work that I often left the office much later than the specified time.

Like a jeweller who recognises a piece of jewellery at first glance, a judge, after four or five years of practice, would know instantly if an accused person is innocent or guilty. That is why wrong verdicts are quite rare. This, of course, is true only about those judges who are committed to being honest at all cost.

– Extracts from the memoirs of Ostad Elahi as judge, Asar ol-Haqq, vol I, ch 24.

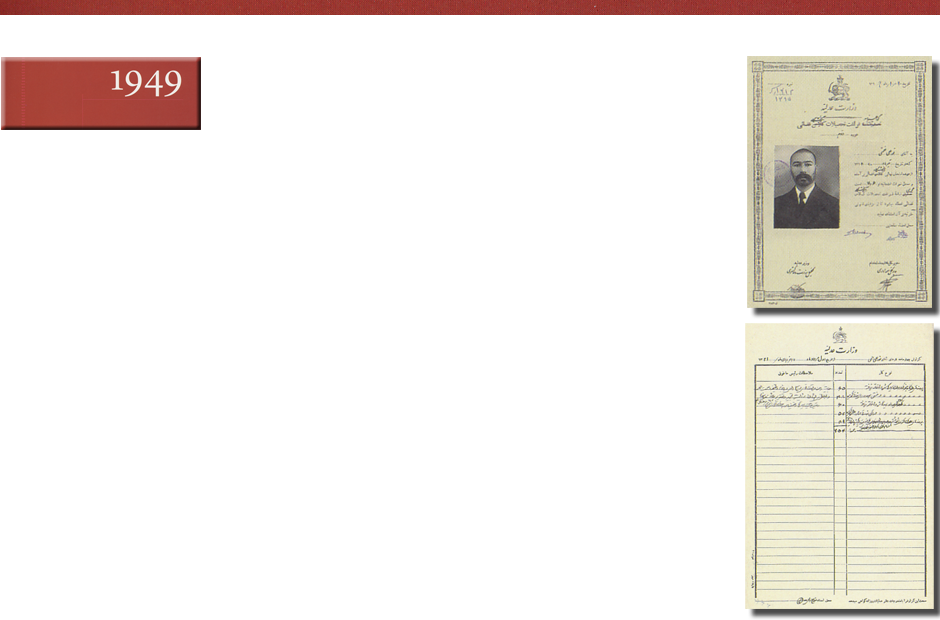

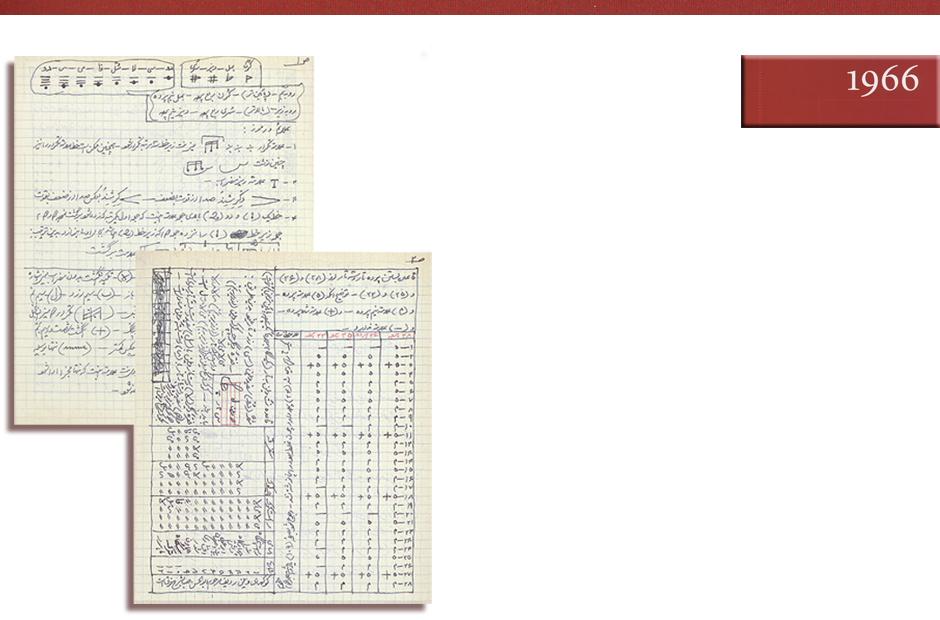

Documents from official files.

In Kerman, there were two large and very influential families, named D and Z. In the days when I presided over the judiciary in that province, at the Ds’ instigation, a garden belonging to the Zs was set on fire and the trees in it were all uprooted.

A complaint was filed with the court. Having received a bribe of 42,000 tomans from the Ds to block the Zs’ case, the examining magistrate cleared the Ds by citing “insufficient evidence” The Zs appealed the ruling and their file eventually reached my desk. In it I found clear proof of their claim. I reversed the ruling and had the file reopened.

On the day of the hearing, so many people from both parties descended on the court that my assistants were frightened. So, I decided to handle the proceedings personally. Finding the moment inappropriate for announcing the court’s ruling, I postponed it until the next day.

That evening, a certain Haji Sh., who was a dervish as well as a chanter of religious odes, came to me and said, “The Ds have asked me to tell you that apart from the 42,000 tomans already given to the examining magistrate, they are prepared to give you double that amount if you confirm the previous verdict. They say that if this offer is refused, they can make use of their connections with some high central authorities and also take action there.” I replied, “Tell them, I’m not afraid of either the Justice Department or of you. Do everything you can, and I will give what I consider to be a just verdict.” Haji Sh. went away and afterwards some people came to speak to me on behalf of the Zs. “We know about the answer you’ve given to the Ds,” they said, But, we’ll pay you more if you uphold justice. I told them to go away.

I learned later on, that the police department, having fears for my safety, had placed guards around my house the whole night. The next day I went to the courtroom. A big crowd, representing both parties was already present. My verdict overruled the decision of the examining magistrate. Ultimately, nothing came of the warning I had received, but the examining magistrate was subjected to a good deal of hectoring; they demanded their money back from him. I called him in and reprimanded him severely.

– Extracts from the memoirs of Ostad Elahi as judge, Asar ol-Haqq, vol I, ch 24.

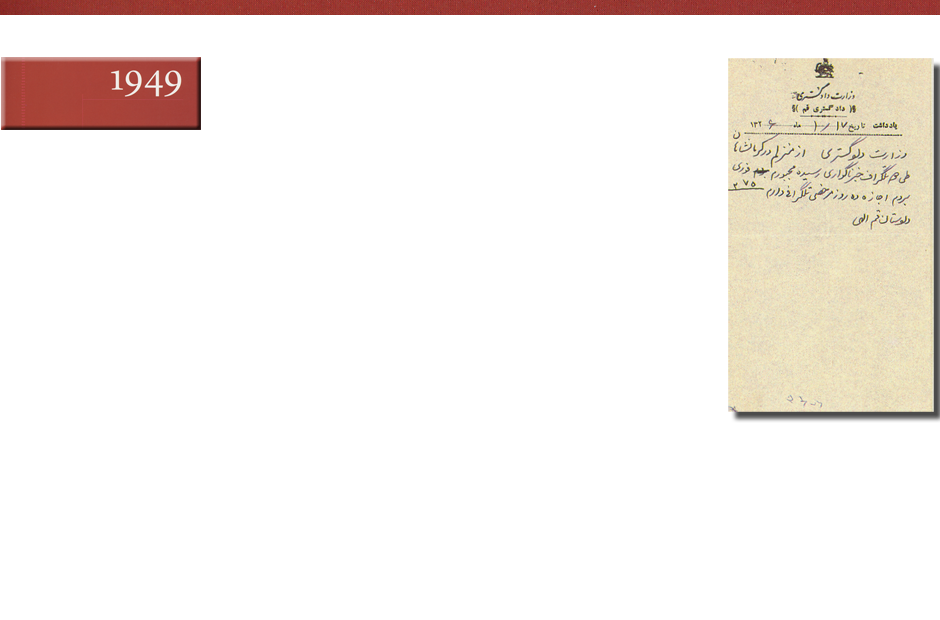

Document from official files.

When I was in Lâr1 there was a young man whose father had died when he was a child. His aunt, as his appointed guardian, had taken control of his entire inheritance, refusing to deliver it to him, even when he had come of age. The aunt had no children of her own, and her high-handedness drove the young man to file a formal complaint against her. In accordance with the law, we took his inheritance away from the aunt and returned everything to the young man.

Some time later, I had a judge’s robe made for me which required patent-leather shoes. Since there was no shoemaker in Lâr, the shoes had to come from Shiraz. It so happened that this same young man was going to Shiraz, so I gave him the money to buy me a pair of shoes. During the trip, however, he ran out of money and spent mine. I was told that he had bought the shoes but sold them afterwards. When he returned, I asked him for the shoes. In response he began to get angry, saying “Are you going to take advantage of your position and put me in jail for that?” “Go away,” I said.

A few days later, policemen brought him into court because he had slapped a respected local merchant in the face in front of others. Now since this young man had been planning to join the Gendarmerie, if found guilty he would have been saddled with a police record that would have barred him from being accepted. The merchant was adamant in refusing to withdraw his complaint. Had the young man been found guilty, I would have had to give him a prison sentence of between eight days and two months. So I turned to the merchant, saying, “So far I’ve not succeeded in persuading you to forgive this young man, but this matter will affect his future. Now, by appealing to your sense of chivalry, may I ask you to forgive him for my sake?” The merchant paused for a moment and then forgave him. So, we released the young man who, feeling ashamed, wanted to come and apologise to me. “Leave it at that,” I said.

Had I sentenced that young man to prison, I would have said to myself thereafter, “You see, you stooped to vengeance!”

The higher the rank (both material and spiritual), the heavier the responsibility.

– Extracts from the memoirs of Ostad Elahi as judge, Asar ol-Haqq, vol I, ch 24.

Document from official files.

1 A city in the southern province of Fars.

I was the Attorney General in Khoramabad. In a dream one night, I saw a highly agitated woman, who said to me “With you here, Mr Attorney General, how is it that I get murdered and my blood is not avenged?” She then introduced herself and told me where she had come from. “They murdered me two days ago and covered up their crime.”

The next day, I asked the police and the forensic department about her. There was indeed a file in her name. It was brought to me at my request and I went through it. Everything had been proceeded with according to the law. An enclosed medical certificate attested to a heart attack. I took no action.

The next evening, the same woman came to me in a dream again and repeated what she had told me the night before. I felt constrained to tell the police and the forensic department that as a result of receiving a report, indicating that the woman had not died of natural causes, I found it necessary to have her body exhumed.

On hearing about the exhumation order, the woman’s relatives descended on the Court House and tried, using every means at their disposal, to prevent it from being carried out. When the exhumation took place, it became clear that the poor woman had indeed been brutally murdered, and that those very relatives were her actual murderers. I re-opened the case and saw to it that justice was fully rendered.

_________________

I was the Attorney General in Qom1 (from January 1946 to November 1947). There were frequent reports about missing objects. One day, a suitcase found at the railway station, containing jewellery, was handed over to the police department. Corrupt police officers looking for a way to split the find between themselves, contacted their counterparts in our department. A distant observer of the whole episode warned me of the matter by telephone. I immediately called the police department and had the suitcase brought over to me. Since I trusted no one, I had to stay in the office and personally make a detailed list of the contents of the suitcase and then seal it up. Only then did I feel at ease.

– Extracts from the memoirs of Ostad Elahi as judge, Asar ol-Haqq, vol I, ch 24.

Document from official files.

1 Qom, a holy city, situated in the south of Tehran at a distance of sixty miles, is an important centre of shi’ite theoretical learning.

Woe to him who would lay his hands on what belongs to an orphan! In my opinion trifling with an orphan’s property is worse than cutting someone’s throat and stealing all his belongings, or committing every possible sin, for an orphan is helpless and vulnerable.

As the Attorney General of Khoramabad1, I had to deal with the case of two brothers, both very rich merchants, one of whom had died long ago, leaving behind five children — four girls and one boy. The other brother had married off two of the girls to his sons and taken in marriage his brother’s widow, leaving the two younger girls and the small orphaned boy unprotected.

Whenever I was transferred to a new post, I would begin my judicial tasks by attending to the affairs of the minors; and that was how that particular file came to my attention. I noticed that my predecessors had examined it, but never followed up their observations with any concrete action. I re-opened the case and subpoenaed the very influential merchant. He came to me, with many flattering phrases on his tongue and warmly declared, “There’s no need for such measures, Sir. My guardianship is in perfect order!” “But it’s been twelve years since you have produced any statement regarding the accounts of those minors who are under your guardianship,” I said. “There’s no need for such statements,” he replied. “My brother’s widow is now my wife, two of his daughters are my daughters-in-law and the others are just like my own children. Yet, let it be as you wish. I’ll obey your orders and bring you a statement tomorrow.”

Document from official files.

1 A city in the Western province of Lorestan.

The next day he came with a large packet stuffed with bank notes. “What is this?” I asked. Lowering his head, he replied, “Just a small present, sir, and there’s no one here, except you and I.” “You’re mistaken my good fellow!” I said, “There is indeed someone else here whose name is God.” I understood then why that file had remained stagnant for so long. He was, however, very persistent. He even managed to persuade the Ministry of Justice to send us a letter of recommendation. But I continued to insist that he should give a full account of what he had done with the inheritance belonging to those minors. Finally, I warned him that unless he did this within twenty-four hours, I would put him in jail. Realising that he was cornered, he said, “Please send a panel of religious authorities to audit the accounts.”

I sent four impartial clerics over to him; they had to work for a whole month before they could come up with some sort of statement. It all added up to an enormous fortune (and this was just the portion they succeeded in examining). I dismissed him immediately and transferred everything to the minors. Only God knows how far he had dipped into their inheritance.

In my opinion, a person in authority who accepts a bribe to abandon an inquiry has committed a greater sin than the person who offers the bribe.

– Extracts from the memoirs of Ostad Elahi as judge, Asar ol-Haqq, vol I, ch 24.

Document from official files.

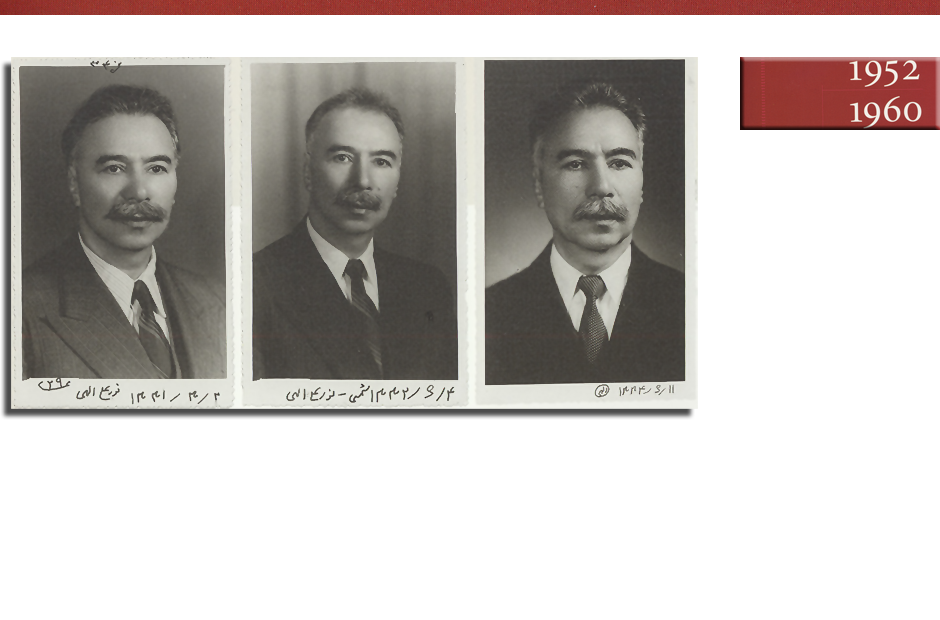

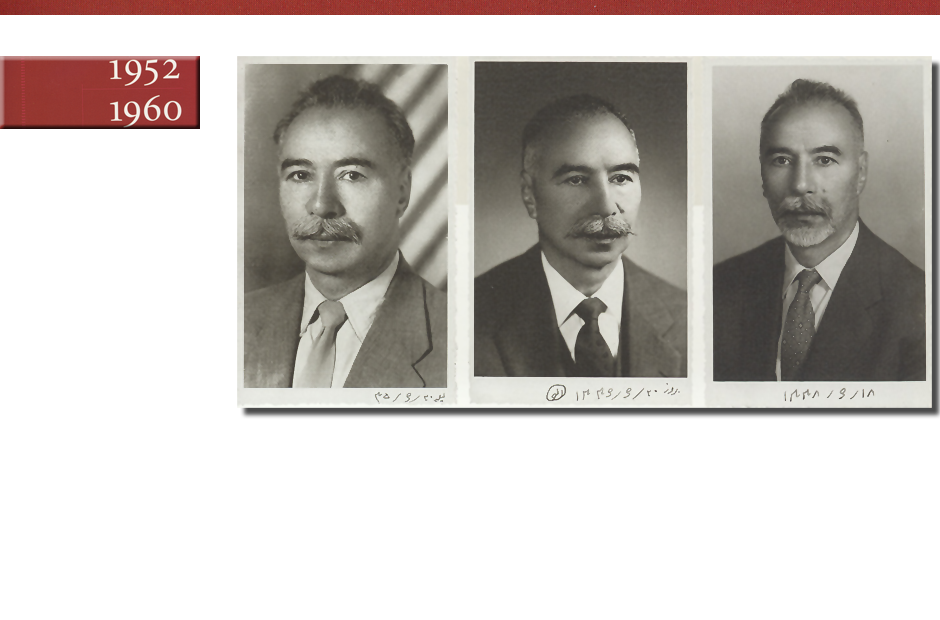

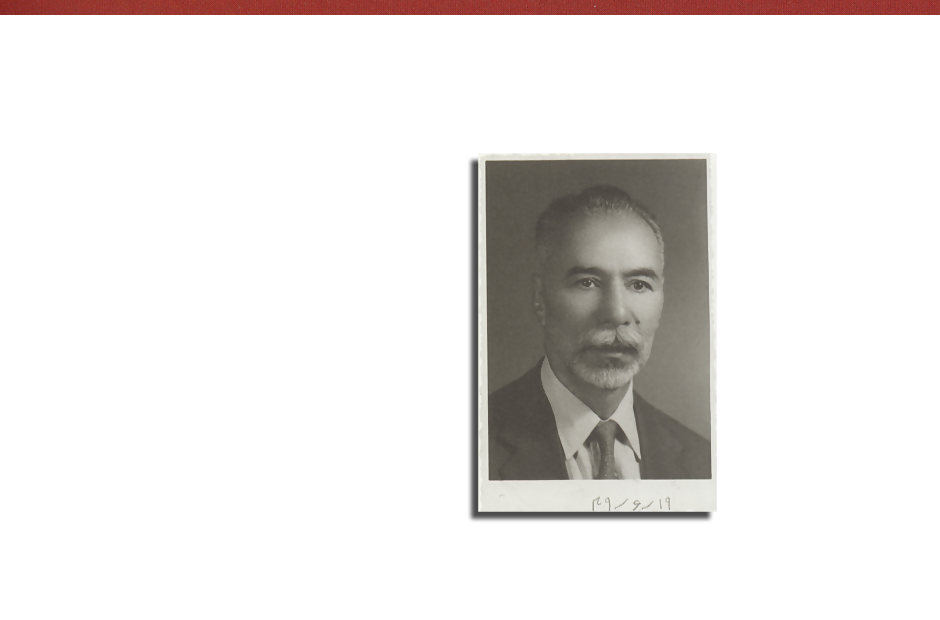

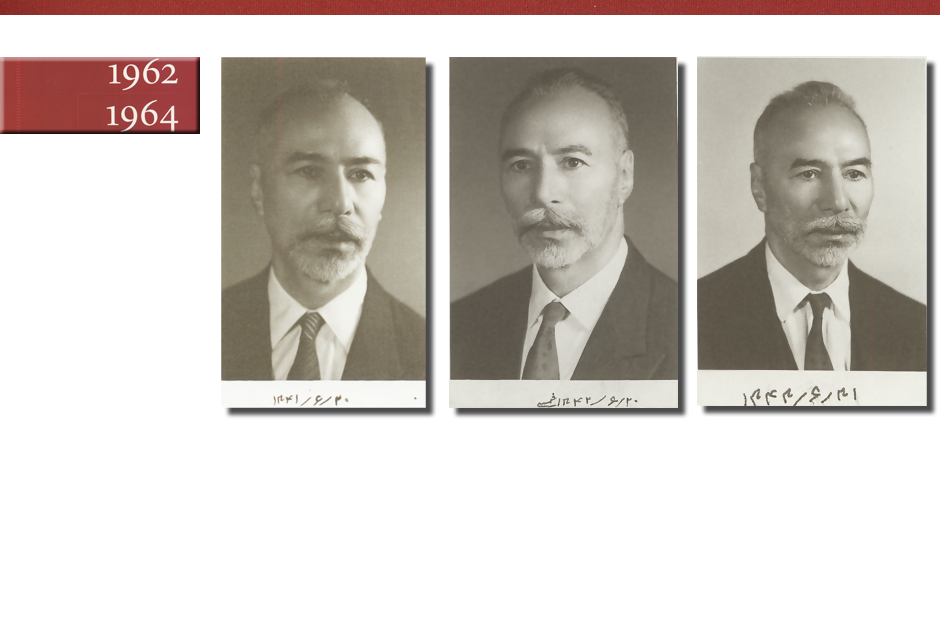

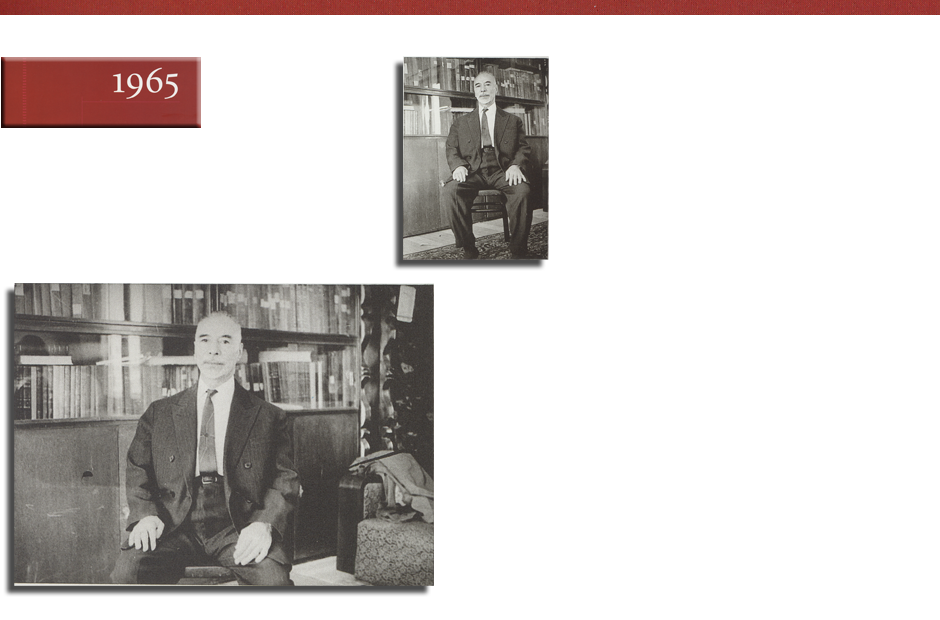

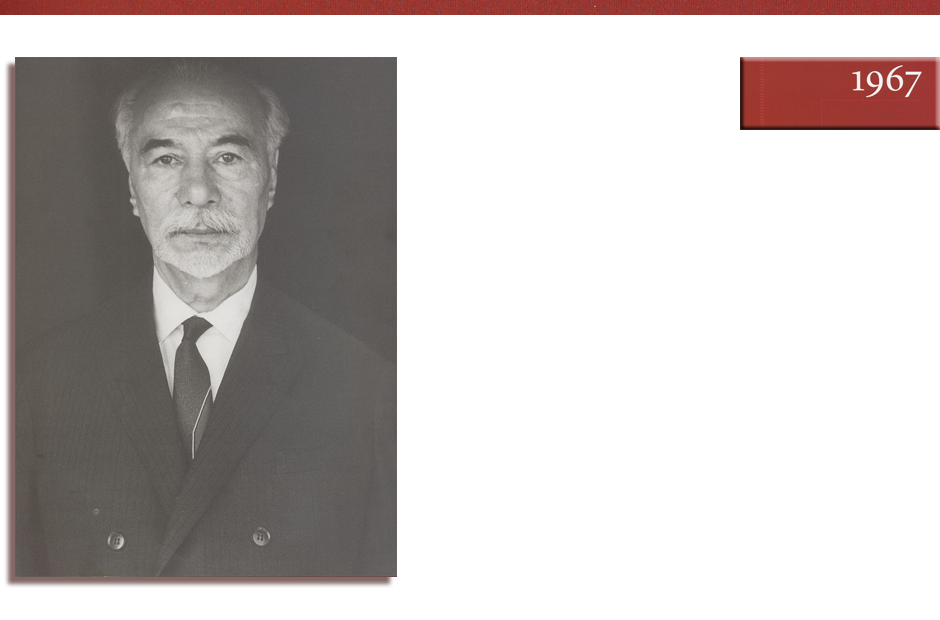

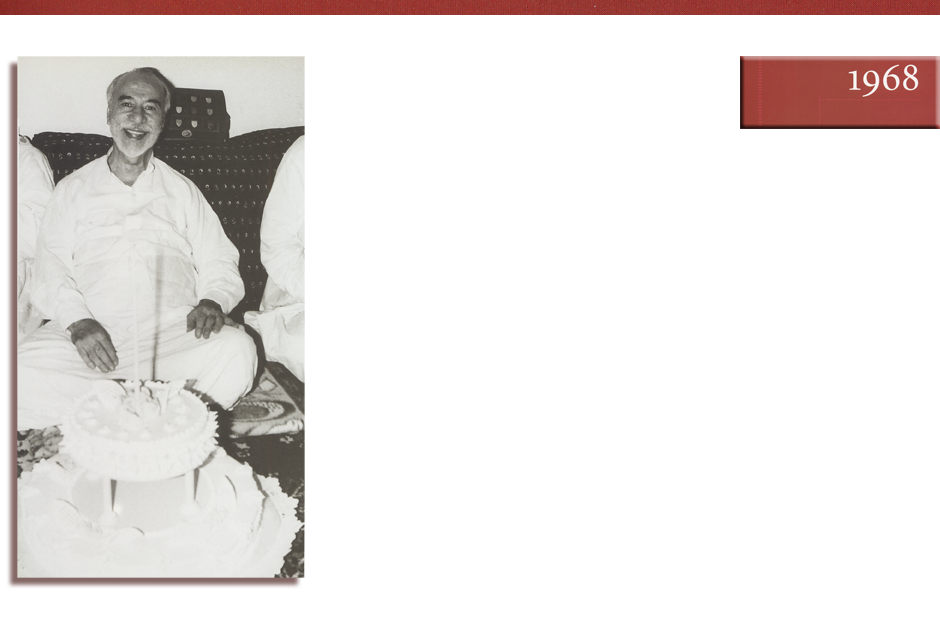

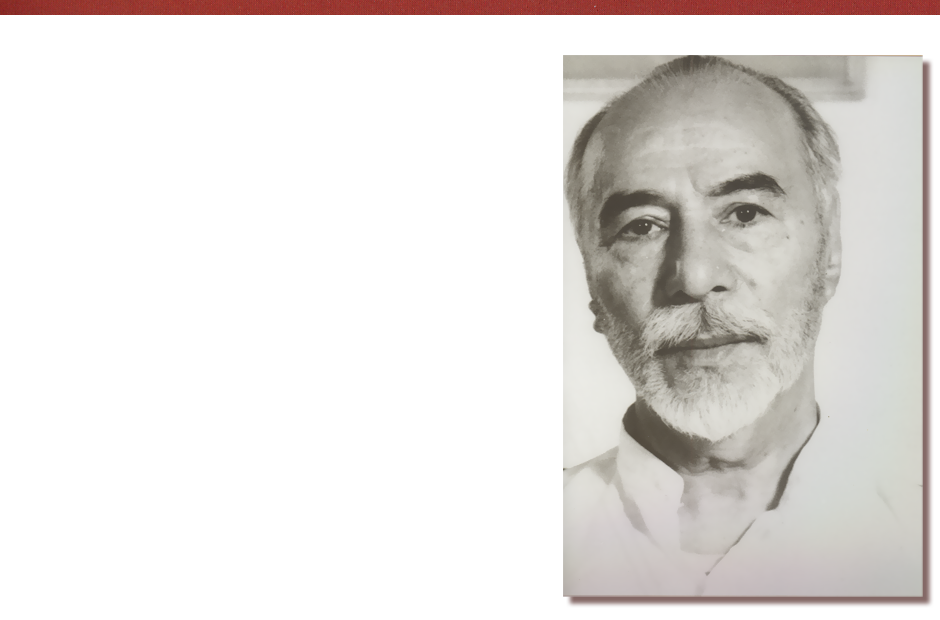

Portraits. Every year on his birthday, September 11, he used to have his photograph taken.

Portraits. Every year on his birthday, September 11, he used to have his photograph taken.

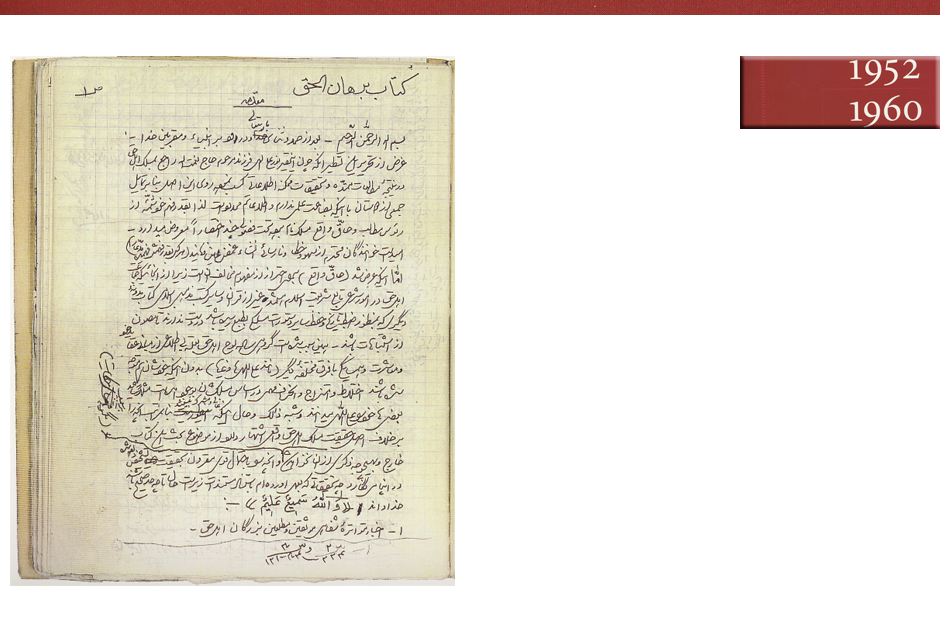

In 1960, his first book Borhan ol-Haqq (Proof of the Truth) was published.

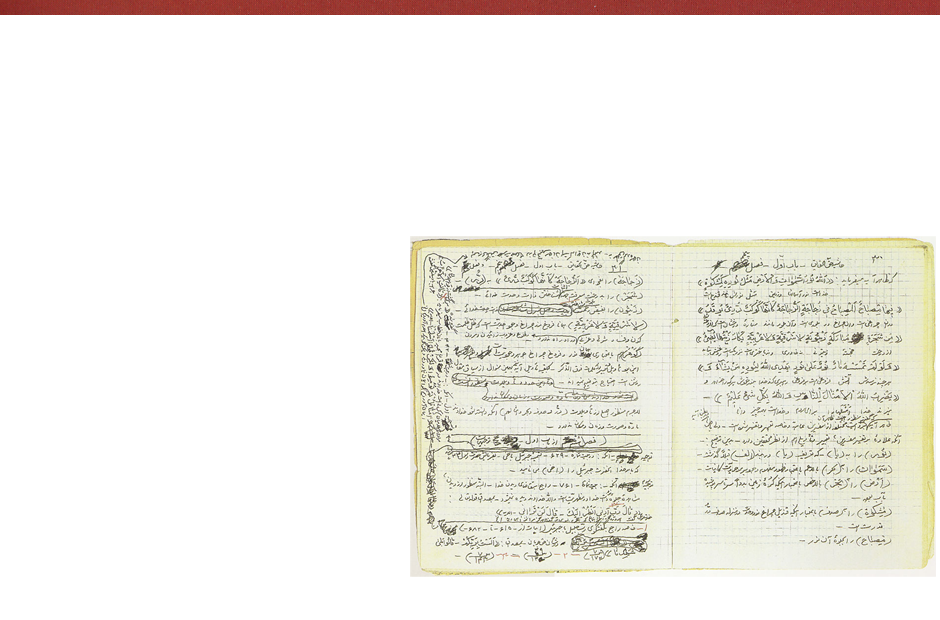

Far left photograph – Extracts from the manuscript of Borhan 0l-Haqq

1962, 1963, 1964. Birthday Portraits.

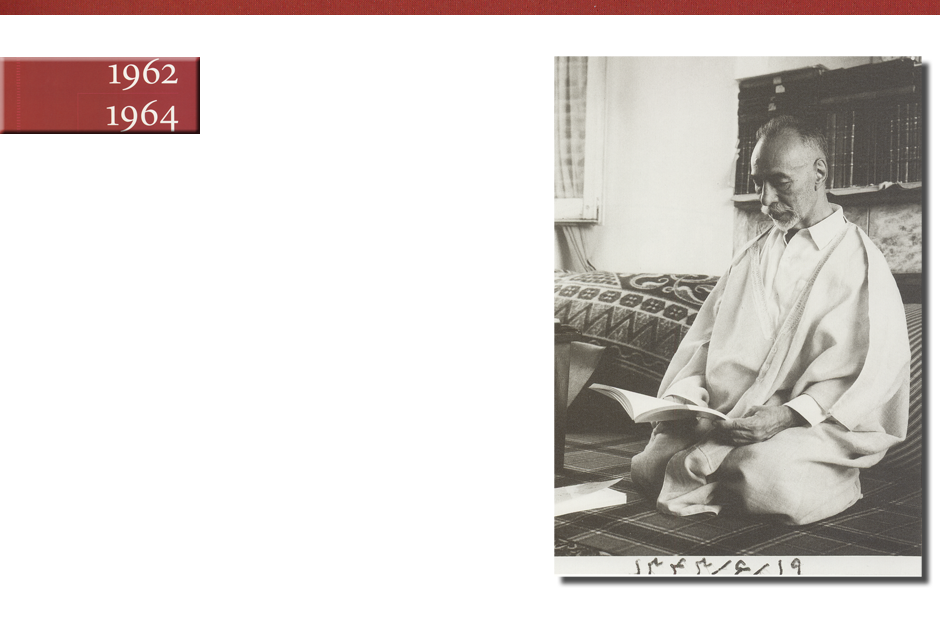

1964. In his room, in his house in Tehran

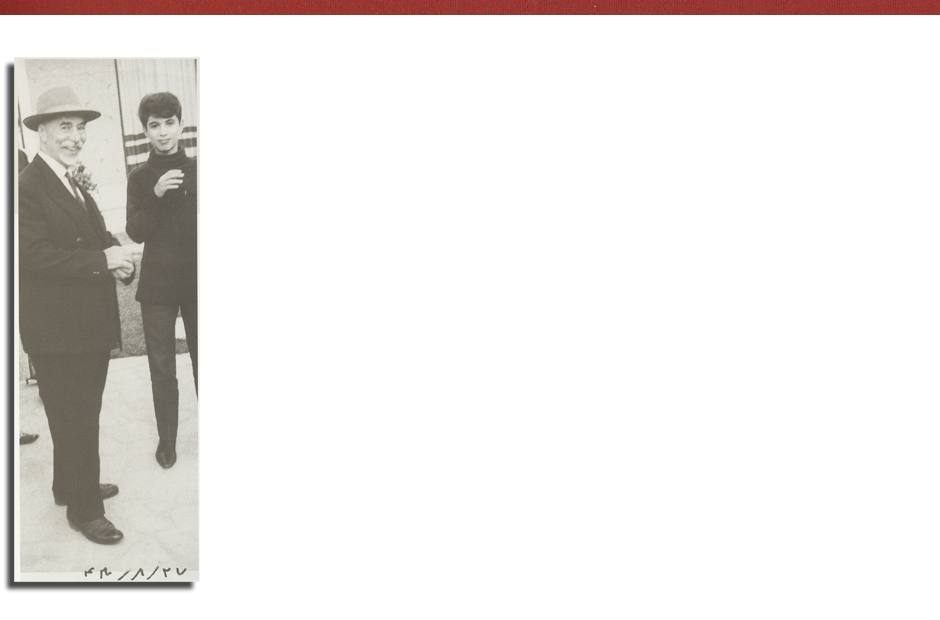

1964. With one of his sons

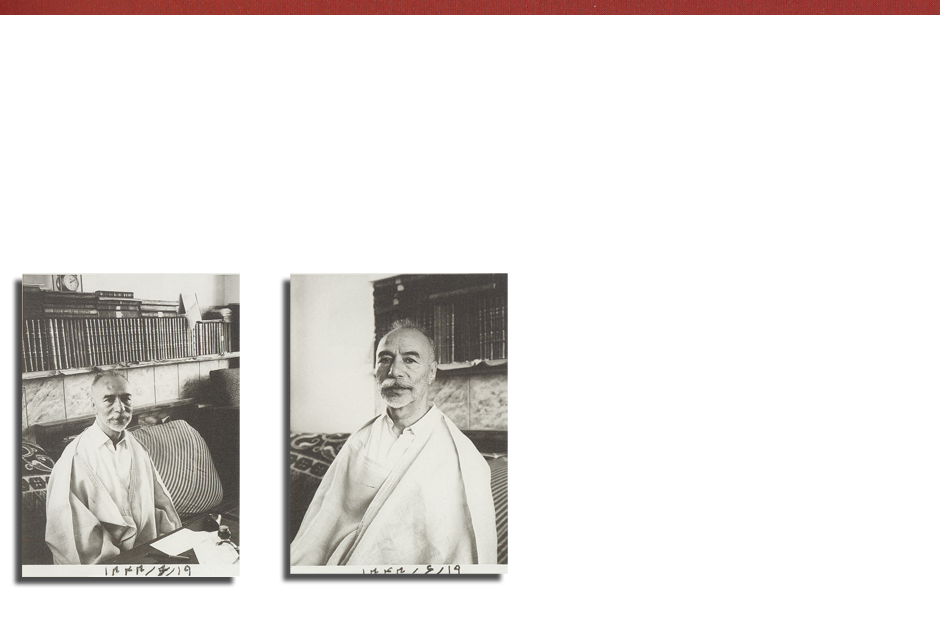

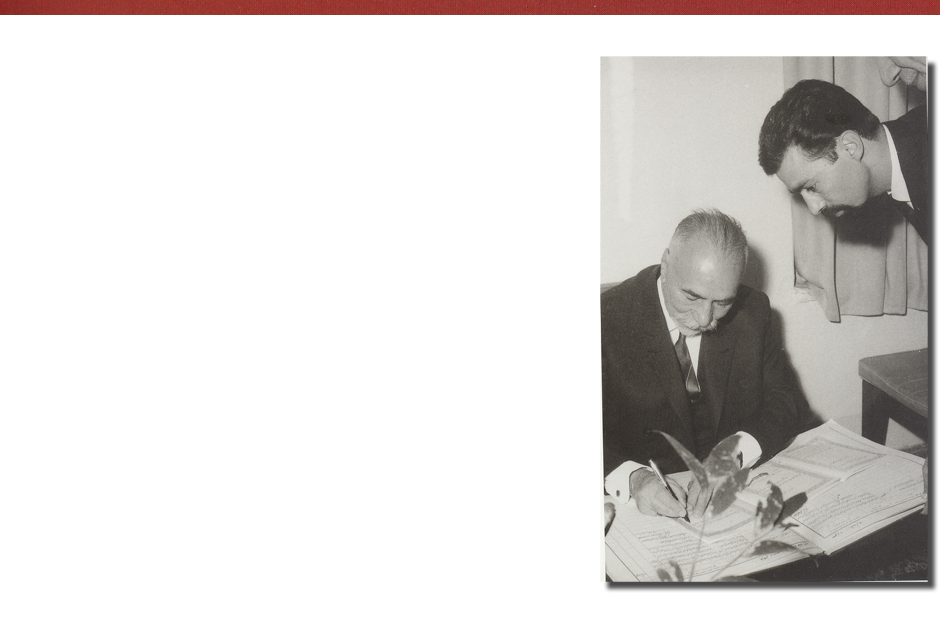

In his library – Signing a contract.

In his study.

In his study. Beside the stove and under the korsi (traditional heating table).

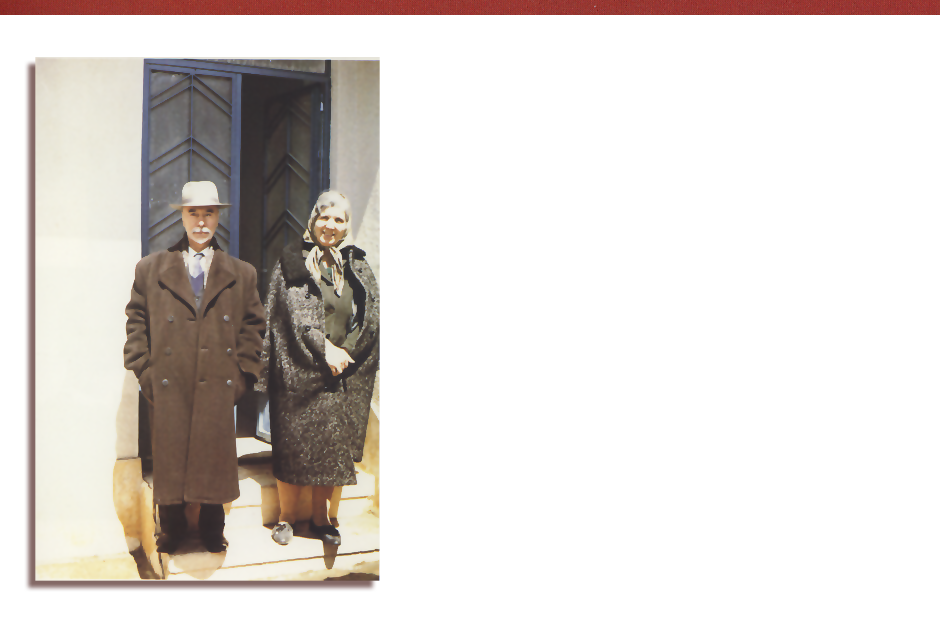

With his wife in front of their house in Tehran.

At a friend’s house with one of his sons.

In Sahneh, near his birthplace. He used to visit his birthplace once or twice a year.

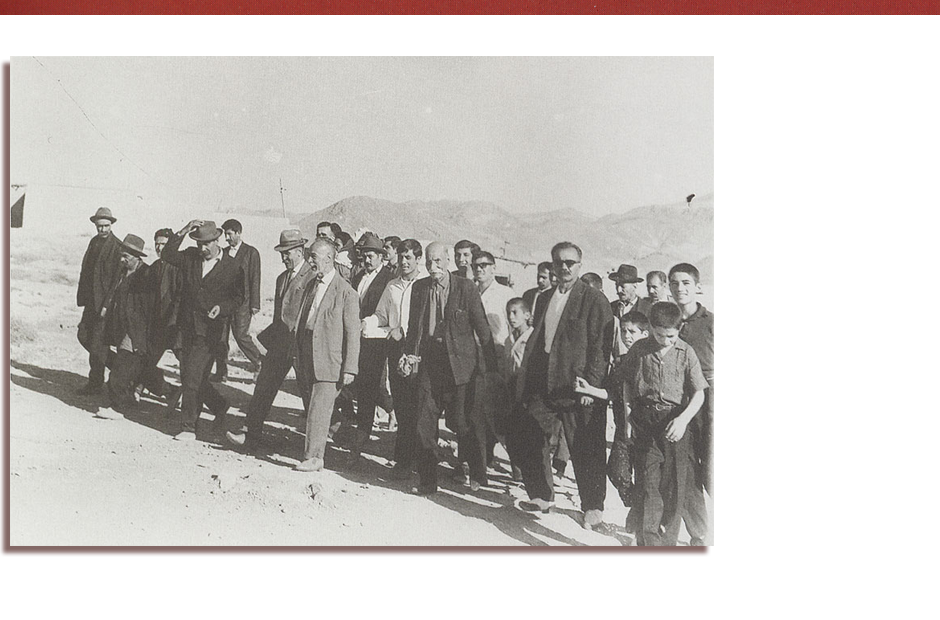

With his followers outside of Sahneh.

With his followers outside of Sahneh.

Top, traditional greeting. The three other photographs were taken at Darband, a shelter in the mountains near Sahneh established by Haj Ne’mat for his devotional practice.

Among followers in Sahneh.

Ethical values belong to the domain of the soul. One must be properly informed about ethical values.

Some years ago, someone by the name of K, belonging to the Gouran1 clan, and very much respected in his own district, was invited to a friend’s house. I was there too, along with some others, including Mr Q. K was handed a tanbûr2 on which he played some dull and sketchy melodies. Mr Q, who had heard my tanbûr before, insisted that I should play too. To spare K from feeling embarrassed, I refused. K, however, thought that I dared not play in front of him. I accepted that and did not play, because if he had heard me play the tanbûr, he would have lost confidence in himself.

Be humble before others and treat them with kindness and courtesy. It is easy to be learned, but difficult to be human. “There’s virtue in humility when shown by the mighty. In a beggar it’s only natural.”3 Never make indecent and shameful remarks and never address people disdainfully.

– Extract from Asar ol-Haqq, vol I, ch 24.

1 One of the many Kurdish clans residing in Western Iran.2 Persian Lute.3 Quoted from Sa’di, classical Persian poet.

Parts of an original manuscript on music.

The traditional tanbûr had only two strings, to which I added one. Tanbûr, setâr and the seven-jointed reed are the most ancient Iranian musical instruments. While playing the tanbûr in devotional gatherings, when I see that some people begin to be over-excited, I change the tune.

– Extract from Asar ol-Haqq, vol I, ch 24.

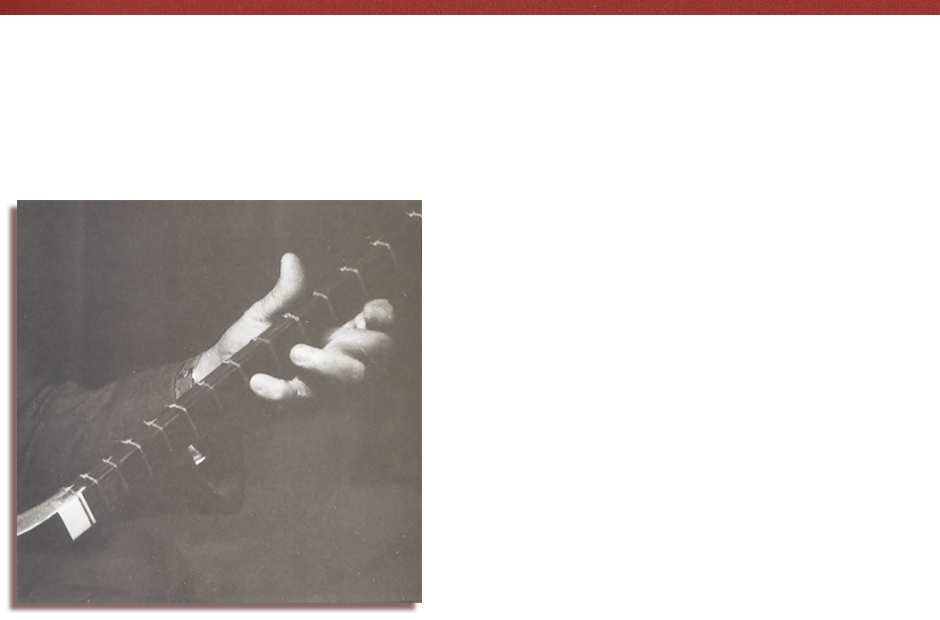

Ostad playing the tanbûr, left hand – Playing the tanbûr, both hands.

There are two things on which my time was really well spent, the tanbûr and spirituality. During my childhood, I would learn whatever my father taught me about the spiritual path. When I reached the age of adolescence and maturity, I already knew enough about the wiles of the imperious self, not to let it have its way. But regarding formal studies, I did miss some opportunities. At the age of thirty two I began my advanced studies, and I had to work very hard.

_______________

I once questioned Rumi 1 about the nature of his dancing. “How was it,” I asked, “that you could manage such astonishing feats of leaping and whirling at your great age?”

“Play your tanbûr,” he said, “and see for yourself how I do it’

“Do you mean to say that you too are familiar with my tanbûr?” I asked.

“I always listen to it,” he replied.

– Extracts from Asar ol-Haqq, vol I, ch 24.

1. Mowlana Jalal al-din Rumi: The great 13th century mystic poet who was also the master of the ecstatic dancing which is at the root of the dance for the present day whirling Dervishes of Konya.

Playing the tanbûr

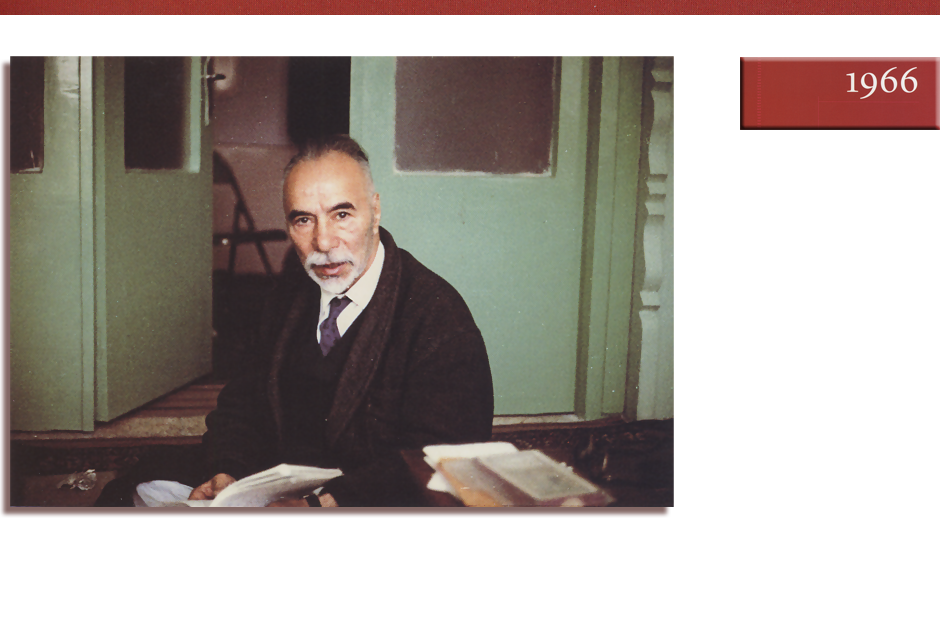

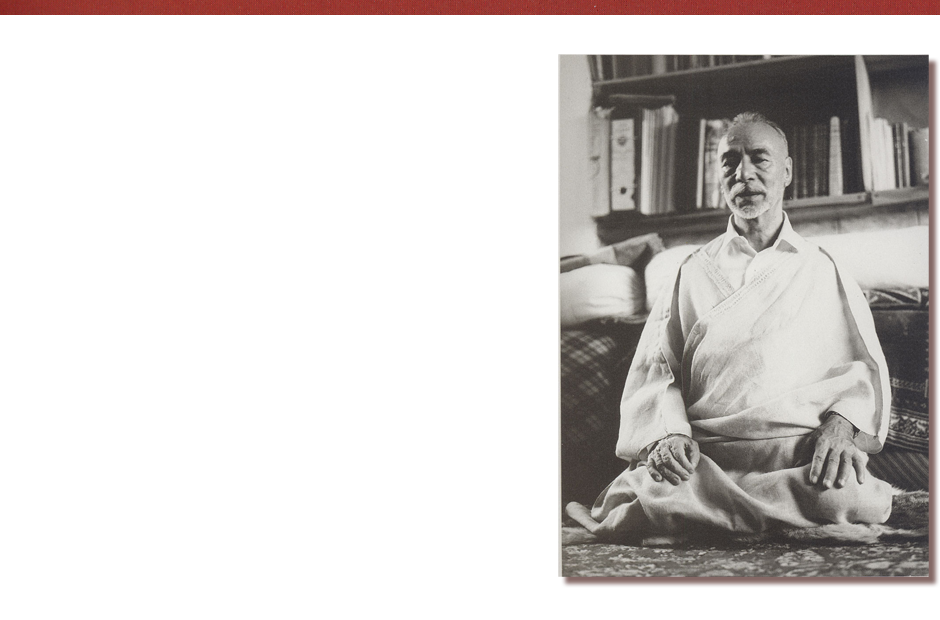

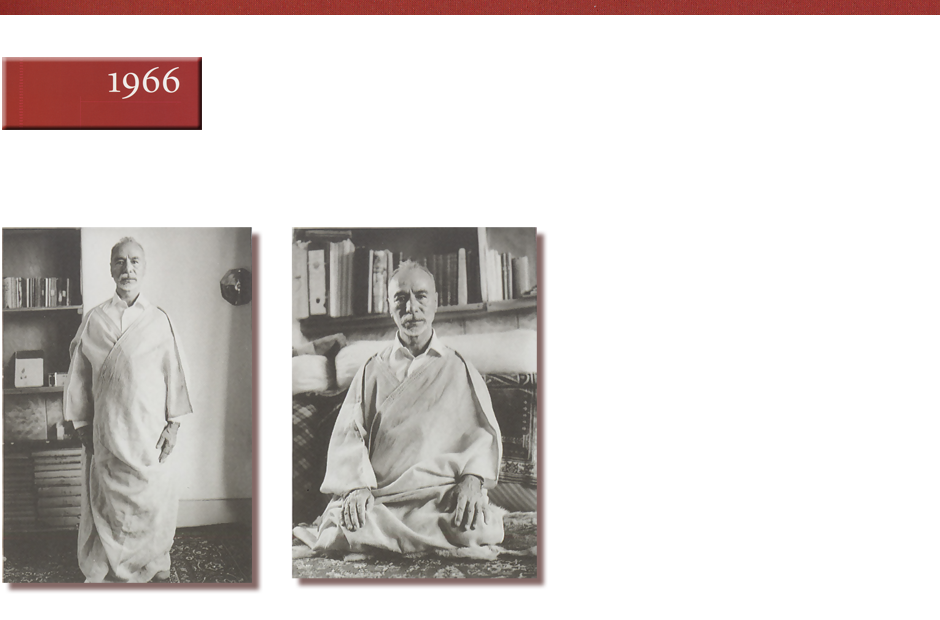

September 11, 1966. In his room

At home in Tehran.

Manuscripts of Hashieh bar Haqq ol-haqayeq (Commentary on The Truth of truths), his second published work.

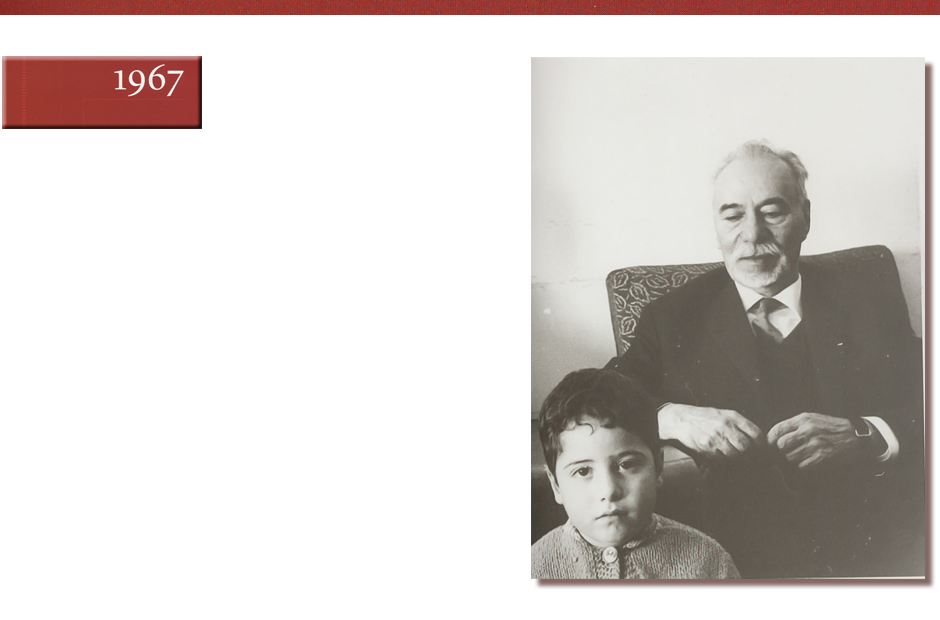

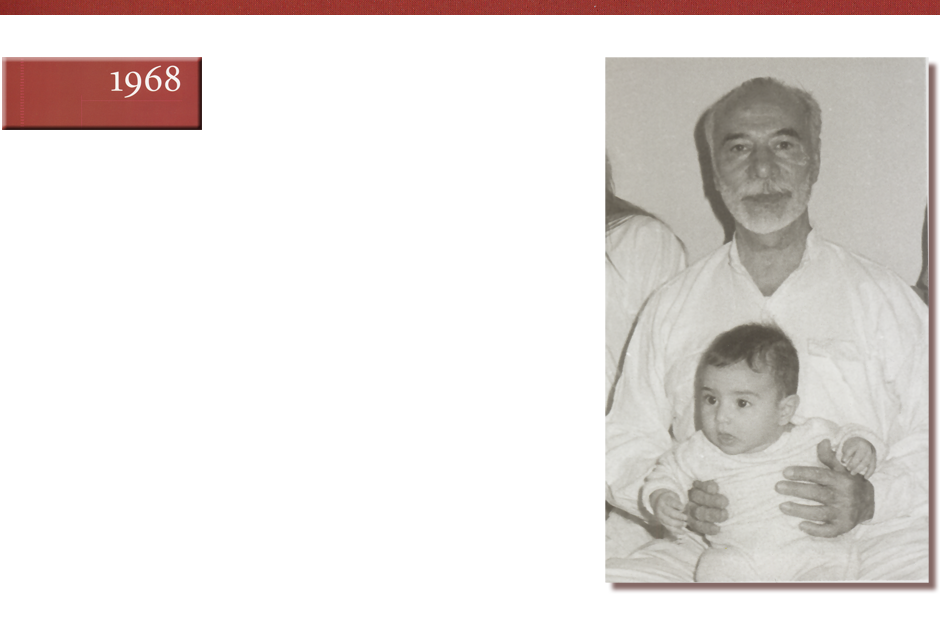

Tehran, at his house, with one of his grandchildren.

On his birthday – With one of his grandchildren.

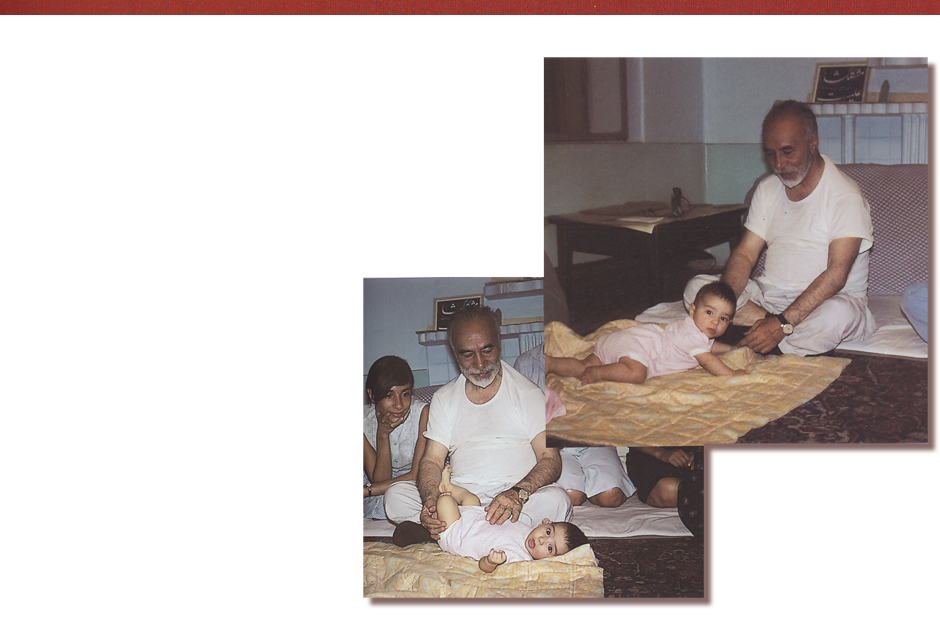

On his birthday – With his youngest daughter and a grandchild. He always used the table in the corner as a desk.

His 73rd birthday – On his birthday, praying.

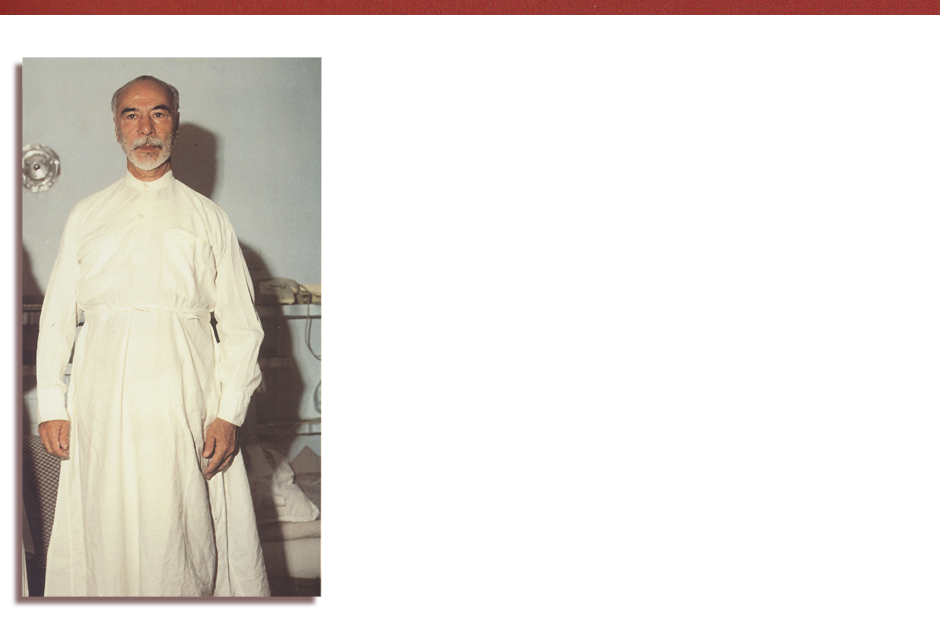

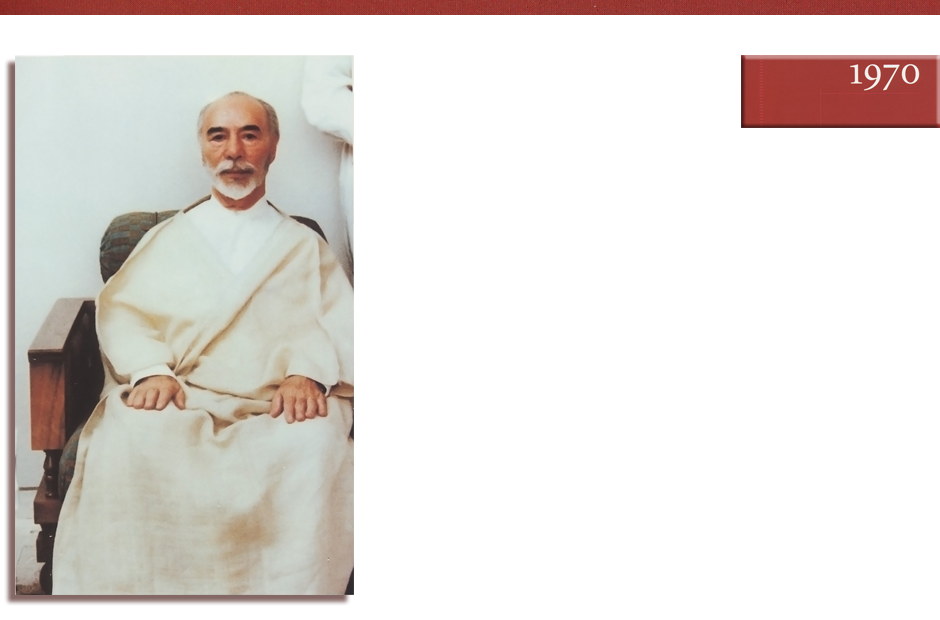

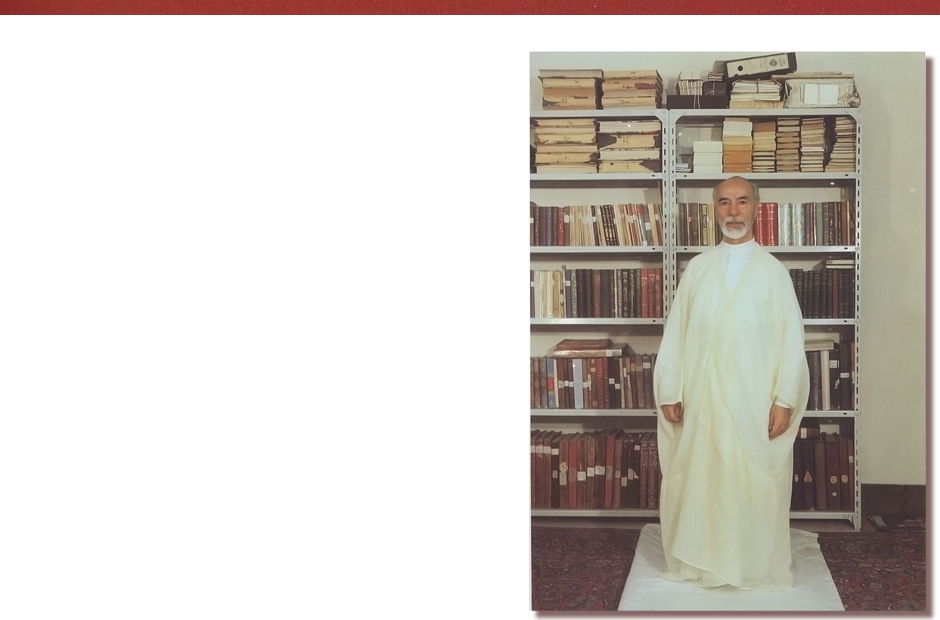

Wearing a white cotton robe, a traditional garment sometimes worn by Ostad Elahi at devotional gatherings.

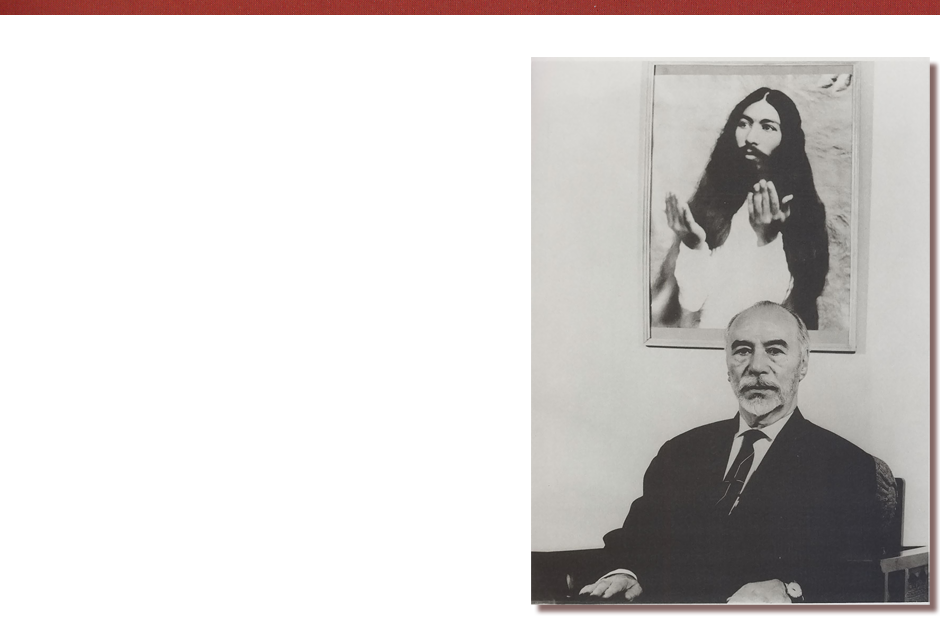

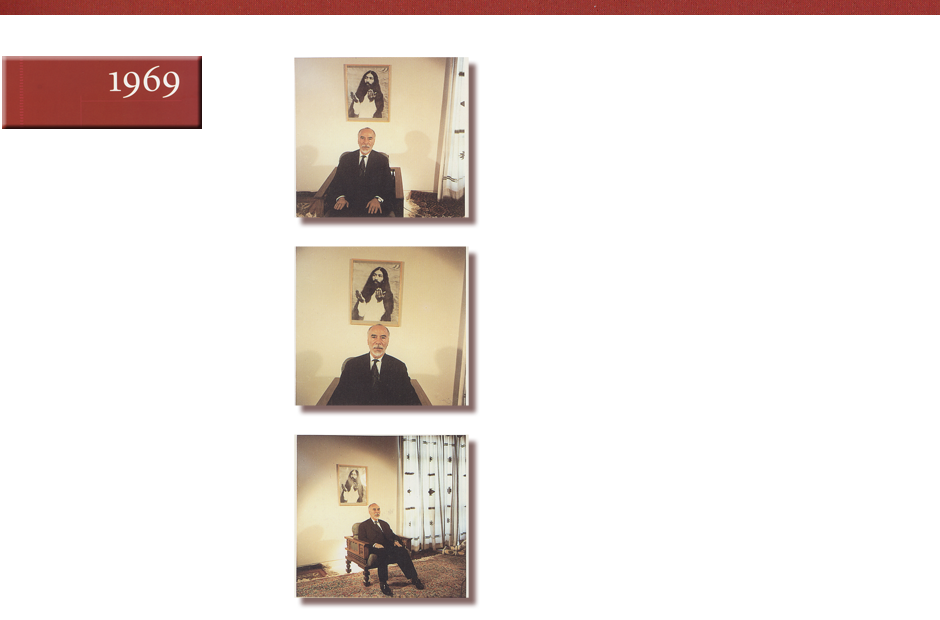

At the age of 74. The portrait behind him is of himself at the age of 26.

Ma’refat-ol-Ruh (Inner knowledge of the Soul), the third book by Ostad Elahi, published in 1969 – Portrait.

September 11, 1969, his 74th birthday.

With one of his grandchildren – In traditional summer wear, at a relative’s house.

In his study.

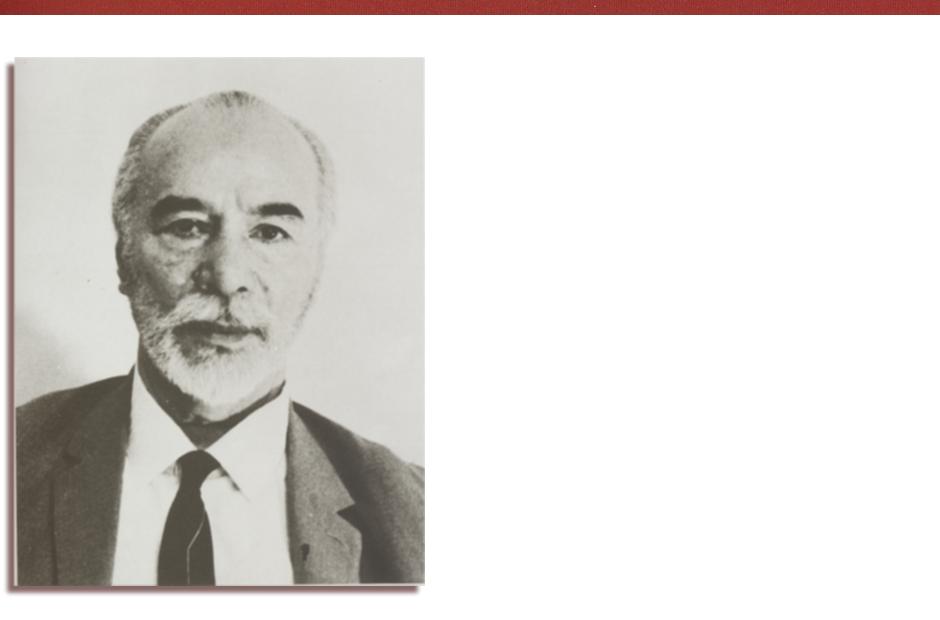

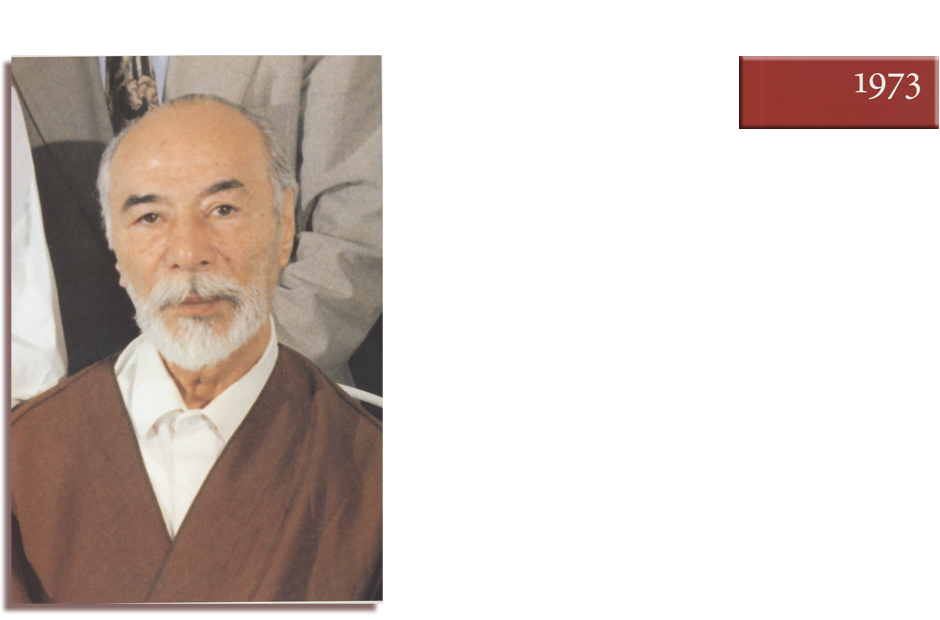

Portraits taken on his birthday.

Portrait.

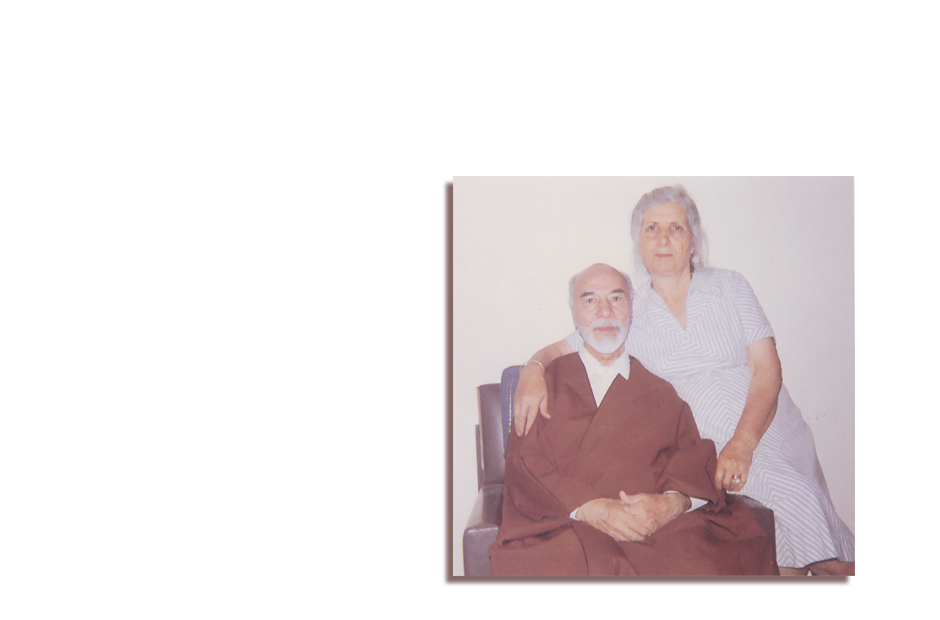

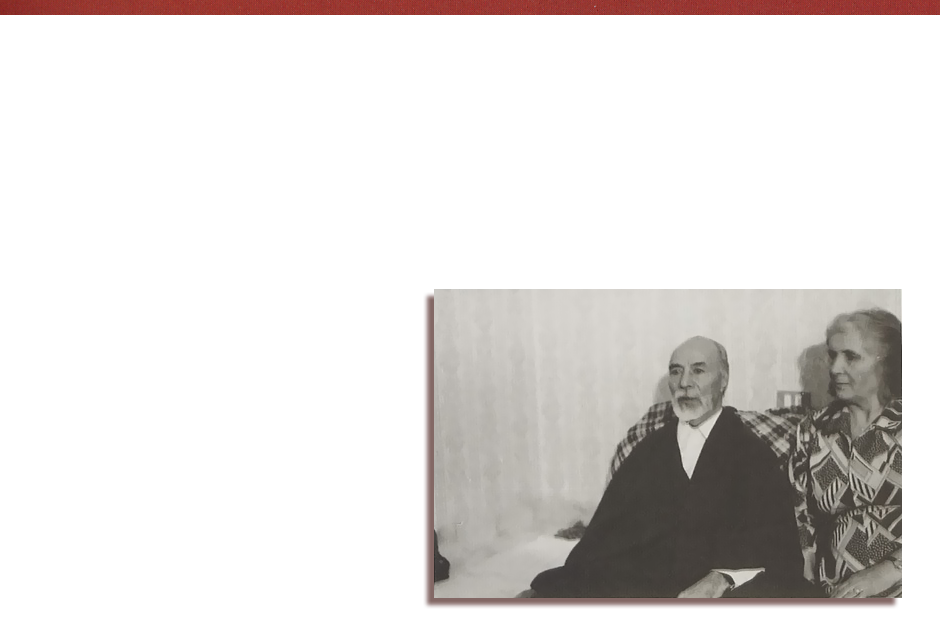

With his wife, on his birthday.

Portraits – His left hand.

Portrait – With his wife.

There is no essential question that I have passed over in silence. All one needs is understanding and will-power. And will-power comes from the soul.

My intention is not to tell stories, but to give guidance, never recommending anything before practicing it myself, never presenting a subject before fathoming its depths, so as to ensure that it is not inconsistent with the laws of this world or the next. I have not imitated anyone. All this is the result of my own observation and experience. In a few words, I have presented the quintessence of spirituality for those in search of Truth.

My words may be trusted for the following reasons:

Throughout my life, when unsure of something, I have never been ashamed of saying “I don’t know”, always trying to ensure the accuracy of my statements.

From early childhood, God had given me the gift of logic, enabling me to produce a rational argument for every subject.

As I had a passion for philosophy, I made it the subject of my studies. I have explored, as far as needed, the pivotal dimensions of spirituality and mysticism.

As a result, both the theologian and the mystic find themselves in agreement with my statements.

– Extract from Asar ol-Haqq, vol I, ch.24.

The narrow lane leading to his shrine.

The shrine of Ostad Elahi in Hashtegerd. 70 km west of Tehran.